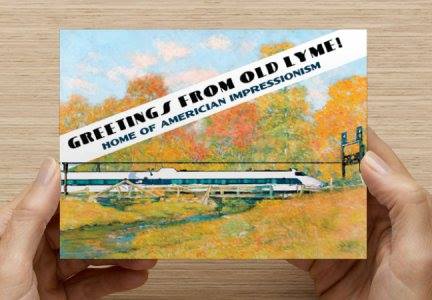

Today, we are publishing a second question and answer (Q & A) piece in our occasional series related to the Federal Rail Administration’s (FRA) proposal to route a high speed rail track through the center of Old Lyme bifurcating Lyme Street just to the south of the I-95 bridge.

We pose our questions to Greg Stroud, who then graciously responds with his opinion. Soon, we hope also to be publishing an update from Old Lyme First Selectwoman Bonnie Reemsnyder.

Stroud, an Old Lyme resident, has taken a deep and enduring interest in the FRA’s proposal and has, in the process, become extremely knowledgeable on the complexities of the project. For regular readers, you will recall that Stroud wrote the original editorial on LymeLine.com that sparked an avalanche of interest in and concern about the FRA’s proposal. The first Q & A we did with Stroud similarly generated a healthy discussion and can be found at this link.

Stroud has also created a Facebook page titled SECoast at Old Lyme where readers can glean a plethora of information about the project and be kept current on developments.

Question (LymeLine.com ): How would you respond to readers, who might make a back-of-an-envelope calculation, and conclude that the numbers for high speed rail simply do not add up? Last December, Congress passed a transportation bill, the so-called FAST Act, which budgets only $2.6 billion over five years for passenger rail along the Northeast Corridor, and yet, NEC Future Alternative 1 (the least expensive high speed rail option) carries a price tag of at least $65 billion. Surely, you can’t build what you can’t fund?

Answer (Gregory Stroud): Well, I’d start by offering a simple equation of my own. Take a look at I-95 today. I think pretty much everyone agrees it’s a disaster. Now imagine how it will look in another 10 years if the population along the Northeast Corridor grows, as expected, by another 12 percent. And in 20 years? An added lane in either direction—at its own estimated $9 billion—only adds so much. If not from rail, where else will we find the needed added capacity?

The Northeast Corridor is a $2.6 trillion economy, every day fed by 7,500 commuter trains, 1,200 Amtrak trains, 70 freight trains, more than 260 million passenger trips per year. Connecticut alone is proposing to spend $100 billion over the next 30 years on transportation infrastructure. Add to that the needs and economies of Boston, Providence, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, with Old Lyme perched somewhere in the middle.

A single day’s disruption—a malfunction of the lift bridge across the Connecticut, or by damage from a storm—comes at its own estimated cost of $100 million. Even the apparently unthinkable “no action” alternative would cost $20 billion.

Of course, Congress will never appropriate enough money to modernize high speed rail along the Northeast Corridor, but then that was never the plan. Instead, the idea is to negotiate a cost sharing between the federal government, the states and operators along the corridor, not just Amtrak, but VRE, MARC, SEPTA, NJ Transit, LIRR, Metro North, Shore Line East, MBTA, and the freight operators.

Another $35 billion of private financing is potentially available through the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing program (RRIF). The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) offers a further $275 million per year.

More financing will have to come from the private sector. Tens of millions each year from utility companies for leasing easements along the rail lines for natural gas, oil, fiber optic cable, an estimated 100 new cellphone towers, and so on. In Florida, high speed rail partnered with the Fortress Investment Group. In Maryland, the Purple Line is a $5.6 billion public-private venture. The Northeast Corridor will require similar financing and investment.

Providing for these investments is exactly why, on a bipartisan basis, the FAST Act included a provision to effectively separate the Northeast Corridor from Amtrak’s other services. Rather than funding rail travel to Omaha or Elyria, Ohio, the Northeast Corridor will keep its steady stream of surpluses (currently about $300 million yearly) in exchange for assuming the long-term burden of its own infrastructure expenses.

But with costs stretching into the tens of billions, why would Connecticut settle for Alternative 1—a plan with few stops and relatively little service for the state? Perhaps it won’t … That said, given the current state of the Connecticut finances, perhaps the plan with the least service perversely best leverages the other states and operators along the Northeast Corridor to help solve Connecticut’s almost unmanageable infrastructure backlog. High speed rail service for New Haven and Stamford in exchange for a more favorable cost-sharing formula. Perhaps. It’s not clear.

Given the stakes, the complexity and scale of such negotiations, it’s no wonder not a single politician above the local level—not Malloy, not Blumenthal, not Murphy, not Courtney—has come out publicly opposed to a new rail route through Old Lyme. Taken as a whole, Old Lyme appears a very small matter in the very large scale of things. But for Old Lyme residents to feel at all safe, that must change.

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Greg Stroud.

Thanks for keeping the discussion going and not making this a single story topic! Transcend the news cycle. A lot of very thoughtful comments as well. Please keep thit discussion going. Thank you.

Thanks, Jon! Much appreciated. We really appreciate how Olwen has brought the community together on this…