Tragic link between the featured artists is that they all committed suicide

PARIS, FRANCE — The art scene in Paris during the last month of 2023 was quite intense. Three major exhibits of artists—coming respectively from France, the US and the Netherlands—attracted a sophisticated, international public. These artists have nothing in common, except that all three of them committed suicide.

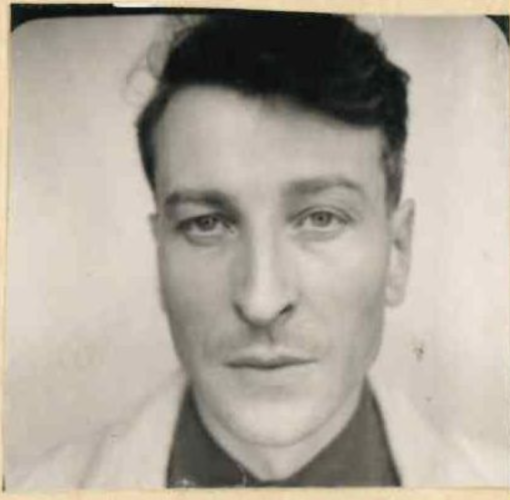

Nicolas de Staël (1914-1956)

Nicolas de Staël is all the rage today in Paris. The retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris is the first since 2003 when the Pompidou Center showed the artist’s early work. De Stael is considered as one of the most famous artists in France today and also the most expensive.

The large exhibit includes works coming almost entirely from private collections rather than from museums, indicating his success on the art market. This may explain the sometimes acerbic comments from art circles. Except for Braque, who became his longtime friend, de Staël was closer to writers and poets than to other artists. In contrast, the reaction of the public was gushing and unanimous enthusiasm.

De Staël was born into to the Russian military nobility in St Petersburg. In 1917, at the age of three, he left Russia with his family. After a few difficult years in exile, he found himself as an orphan at the age of eight. Wealthy friends, who welcomed Russian immigrants, helped him attend an upscale school in Brussels.

At the age of 23, he folded up his more than six foot five frame into the tiniest of all French cars—a deux chevaux ( a two-horsepower) Citroën—and drove to Spain on the first of his incessant travels, always searching for the perfect light. What he discovered in Morocco made him throw out everything he learned during his three years of study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He painted eight hours a day and destroyed everything he painted.

His life story reads like a Russian novel, full of passion, despair and drama. His flamboyant and vibrant personality was like a magnet, attracting relatives, lovers and friends and contributed a great deal to his fame as an artist. Disregarding morality conventions, he fell passionately in love with married women. The first one was a young painter, Jeanine Guillou, an adventurer, touring the Sahara desert on the back of a donkey with her husband, also a painter.

After her death in 1946 and the difficult years of the Occupation of Paris by the Nazis, he married Francoise Chapiton, 21, who was teaching English to his stepson Antek and had three children with her. A few years later without qualms, he would leave her and his three children and engaged in another passionate liaison with a married woman, Jeanne Polge.

A visitor to the exhibition is struck by the unusual journey of the artist’s creation which broke the traditional path from figurative to abstract and therefore did not fit into the accepted categories. During his earlier period, de Stael had produced a majority of black and white drawings, graphic work and then one witnesses an explosion of spectacular colors and a return to figurative work.

Actually it is deceptive:since, from a distance, landscapes, architecture, scenes with people or with activities—like a port, or a football game—may seem like figurative representations created “after the motif” but, on looking more closely, the scenes are, in fact, made up of geometrical shapes, which are close to abstraction. One of the earliest paintings where he used color was done in 1933—in the “Arbre Rouge ” (the red tree), red paint drips and makes the tree look as if shedding red tears.

His way of painting was unique. He worked on several paintings at the same time, borrowing from one to modify another. A buyer would be surprised to discover that the work he purchased from the artist was different from the one he saw at first.

Even his studio was out of the ordinary. Located on Rue Gauguet in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, close to Rue des Artists and Parc Montsouris, it had an incredibly high ceiling of eight meters. An art historian compared it to a well, a barn or a chapel.

In 1953, de Staël presented his works in New York and was celebrated by an enthusiastic public and rave reviews in the New York Times. But de Staël’s temperament clashed with art merchants. He disliked the way they speculated on his paintings even before seeing them. There was a great deal of tension at the time of hanging the paintings, which de Stael was used to insist on doing himself. Nevertheless the exhibition of 36 paintings was both a triumph and a financial success.

In 1954 he bought Le Castelet, Menerbes, a fortified manor perched on a rock in the Luberon region of southeast France. The family still owns it today.

In 1955, he continued his frenzy of travels and painting. He rented a studio in the ramparts of Antibes, overlooking the Mediterranean. Ten years earlier, Picasso had created his art studio in the Grimaldi castle also in the ramparts. Antibes was founded by the Greeks in the 5th century BC, under the name of Antipolis.

On the 16th of March, 1955, de Staël commited suicide by jumping onto the rocks.

The de Staël exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art is unusually large. It includes 11 rooms and covers his entire life. One is literally overwhelmed by the masterful works created during his last few years, painted in a wide spectrum of dazzling colors. Here are but a few of them.

“Agrigente”, 1954, 60x81cm .This Sicilian landscape, is simplified to the maximum. the colors are imaginary (purple sky, pink road, yellow hillside). An historian describes the choice of colors of de Stael as a “crashing wave of emotions.”

“Temple Sicilien”, 1954, 73x100cm. The colors are golden, softer, the architecture reduced to simple lines.

“Le Fort Carré d’Antibes”, 1955, 114x195cm. A symphony in blues and whites. The paint is light and fluid. Not much figurative work in this one, mostly geometric shapes floating between sky and sea.

“Ciel à Honfleur”, 1952, 100x73cm. The softer. shades of blues in horizontal bands under the pale sky of Normandy.

“Marseille”, 1954. 80.5x60cm bright primary colors, houses are just cubes, the Mediterranean sea is a flat deep blue

“Parc des Princes”, 1952, 200x350cm. France-Sweden soccer match. One of the master pieces of de Staël. The match takes place at night under spotlights. A ton of muscles fly around the green grass of the stadium. After many sketches, the final painting is an abstract composition of colored energy. At the 86th minute of the game France lost to Sweden.

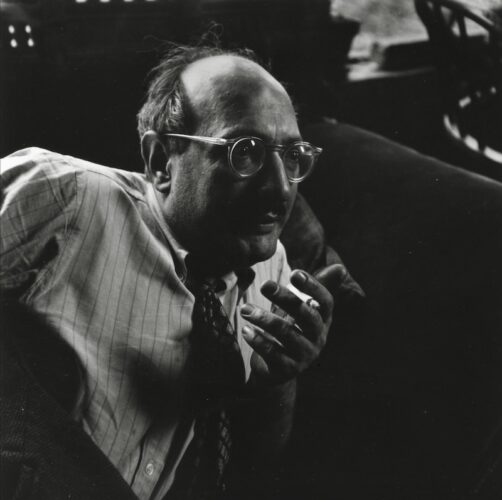

Mark Rothko (I903-1969)

The Rothko exhibition is the blockbuster of this winter in Paris. Parisians have become accustomed to these spectacular events taking place in the museum of the Vuitton Fondation. Since its opening in 2014, it has held other breathtaking exhibits such as the collections of the two most important Russian art collectors of the Tsarist era: Morozov and Shchukin.

An aerial picture of the Bois de Boulogne reveals that the spinnaker-shaped museum created by Frank Gehry is the only building peeping out of the green expanse of the forest. How did they ever obtain permission to build there? The fact that Bernard Arnault, the owner of LVMH—which stands for Louis Vuitton Moët and Chandon—was the richest man in the world until April 2023 perhaps helps explain why.

Twenty four years ago, the Museee d’Art Moderne in Paris had presented a full retrospective of the artist’s works. So, why a repeat in 2023? The long lines of visitors attest to the fascination of the Parisians for the American artist.

Christopher Rothko, son of Mark and co-curator of the exhibition, is playing an essential role in the present exhibition since he contributes the inside story about his father’s personality and the struggles in his artistic career. “It is a miracle”, he explained in an interview, that we were able to obtain 60 percent of the works we wanted as well as several never seen before in Paris. Besides, he added, the Fondation Vuitton helped negotiate loans, which usually have an exorbitant cost.

The Frank Gehry structure is perfect for an exhibition of this size. It allows for an easy flow of the visitors who can access painlessly the five levels of the display, thanks to the all-glass elevators located at strategic places. Personally I wish the confusing layout of the Orsay museum, with its cramped rooms, was more like this.

Learning about Rothko is to attend a course in the history of American art in the 20th century. Marcus Rotkovich Rothko was a scholar, a rebel, and a pioneer fighting for his deep philosophical and social convictions. In 1913 his family emigrated from Latvia, which was then part of Russia, to Portland, Oregon. A brilliant student, he attended Yale for three years. Until 1950 he taught children in the Brooklyn Jewish Center Association.

The exhibit starts with a huge room where his early works are exposed . For 20 years, he was a figurative artist, painting portraits, urban scenes (such as his subway scenes) and landscapes . He also liked to draw archaic figures and monsters inspired by his readings of Nietzsche and Aeschylus . He was most impressed by European artists like Matisse, Miro or Marx Ernst, the Surrealists, and later by the generation of artists—mostly Jewish—who left Europe in World War II.

In 1946 he began his “multiform” series and his definitive evolution toward total abstraction, which art historians call his “classic period” This is the period we are most familiar with, characterized by his “fields of color” .

There was a love-hate relationship between Rothko and New York. He found his inspiration in the town but was highly critical of New Yorkers for their mercantilism, calling them “shopkeepers.”. He hated the frenzy of his life as an artist. But American art was enriched by the stands he was taking.

In 1950, the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized an exhibit entitled: American Painting today” and did not even mention abstract art. Rothko joins the group of 19 “angry artists” , including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Koonig, rebelling against the conservatism of the Met. And today, what does the visitor to the Met or MoMA see? The works of Rothko seem to form the core of those museums’ collections.

The monumental sizes of Rothko’s paintings tend to overpower the viewer. One does not look at Rothko’s painting, wrote an art critic, but enters them. In the small “Philips room”, a simple bench invites the viewer to sit in front of a Roth’s painting and meditate .

The range of colors, from the luminous orange, to the maroon to the grey and black , has a strong impact on the feelings of the spectator. The canvasses are totally covered with paint The demarcation line between different strata of colors seem out focus and a zone with a fluffy texture. In the room at the upper level of the exhibition, his paintings are the most severe. We see a black sky and a grey earth transporting us into wnat one could describe as lunar scenery. The Giacometti statue of “man walking” add sto the somber feeling

Probably the most spectacular event in his career was the commission he received in 1958, to create murals for the elegant Four Seasons restaurant of the Seagram building on Park Avenue, between 51st and 52nd streets. Mies van der Hohe was the chief architect of the 37-floor skyscraper and Philip Johnson was his associate . Van der Hohe was German and the last director of the Bauhaus school in Berlin before it was forced to close by the Nazis in 1933. The innovative design of the Seagram was a steel structure on pillars with a reinforced concrete inner core. Rothko worked for months on the project in an oversize studio he had rented for that purpose. Then he abandoned the project. Later he donated nine maroon murals to the Tate Modern in London. The nine maroon murals are part o the Rothko exhibition on loan from the Tate.

His very last project, was “The Rothko chapel” in the Saint Thomas University in Houston commissioned by sthe extremely rich art collectors John and Dominique Menil (she was the heir to Schlumberger) .

At age of 66, in 1969, he committed suicide in his studio by overdosing on barbiturates and slashing an artery in his right arm.

Gallery talks, offered by art specialists or “mediators”at every level of the exhibit, provide some helpful guidance to the general public on how to analyze one’s emotions when trying to comprehend Rothko’s “Abstract Expressionism”

Vincent Van Gogh’s at Auvers-sur-Oise ( May 20—July 29 1890)

At the Orsay museum, the exhibit of the last three months of Vincent Van Gogh at Auvers-sur-Oise leaves the visitors dumbfounded at how the artist, whom we all know so well, could still impress us with paintings never seen before.

After a one-year, self-imposed stay in St Remy-de-Provence psychiatric hospital, the prospect of living in the small village of Auvers-sur-Oise around 30 miles to the northwest of Paris, and being totally free to go and plant his easel to paint wherever he pleased, was most enticing. His brother, Theo, could visit him often since Auvers was easily accessible by suburban train from Paris.

In Auvers, Dr. Gachet, who was to treat Van Gogh, became his close friend. They shared a mutual interest in Impressionist painting and even their neurasthenic (neurasthenia is a condition characterized especially by physical and mental exhaustion) tendency. Theo, who had made all the arrangements for Vincent’s stay, was optimistic as to the improvement of his brother’s condition. in such a setting.

One must go through a one small room called, “La Palette” before seeing the main exhibit for two reasons: first, saving hours of waiting in line and second, the short, three-dimensional, virtual experience conditions the visitor to plunge into Von Gogh’s haunted world.

You live through intense, almost scary, moments, with the heavy head-set on. You open an elegant, white door with a digital hand and enter a parlor furnished with a piano, a desk and a few chairs. Next, you are transplanted into the wilderness. A palette appears on your left and moves toward you, it becomes huge and threatening, with heavy blobs of paint on it. You are being attacked by it. You find yourself in a forest, surrounded by trees. Slowly you are going down, going through a layer of roots, menacing like a bunch of wiggling giant worms.

Or to use the words of Guillaume Morel’s, a regular contributor to the magazine “Connaissance des Arts,” “gnarled roots, charred trunks, twisted branches.” You are pulled down lower and lower into a bottomless pit, a wreath of trees above your head closes up the view of the sky. Still shaking, you return to the parlor. Now you are emotionally ready to affront the mob scene of the Von Gogh’s exhibit .

The theme of the small format paintings is the village, with its streets, houses and walled gardens, and the fields nearby. One of the streets is animated by two black figures of old women, followed by two young pony-tailed girls dressed in fluffy, white dresses. The 13th century church seems to be aggressively pulsating with life. On the outskirts of the small town, sleepy thatched roof farmhouses and cultivated fields seem peaceful at first.

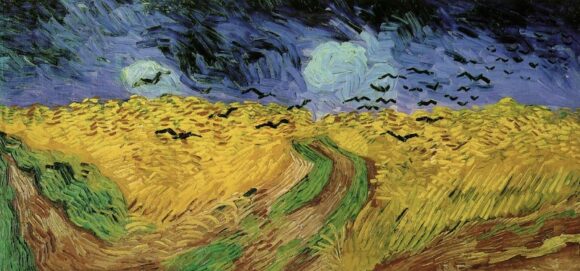

But the agitated brush strokes of Van Gogh turn the few trees into flames, the cottages about to collapse under the weight of their roof, the skies are torn with bizarre and tormented hieroglyphs. The use of aplats or flat areas of paint by the artist to picture the calm fields and sheaves of wheat left by the farmers are soon replaced by a stormy wheat field swept into a storm—a splash of yellow dotted with the black dots of the flying crows.

This most famous painting of all was long believed to be Vincent Van Gogh’s last one. No more. On July 27, 1890, the artist painted “Roots” (the painting the visitor suffered through during the virtual experience of La Palette). Later on that day Van Gogh shot himself in the chest. The painting was found on the easel after his death. He died two days later .

And let me leave you with this extraordinary fact—in the 70 days he spent at Auvers, Van Gogh created 74 paintings … more than one a day.

Editor’s Note:This is the opinion of Nicole Prévost Logan.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes an occasional column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.

An excellent article regarding the three artists. I knew not the artist Stael. But I can understand the shared feelings and art of these men.

Permit me an exception to the writer’s praise of the Foundation Louis Vuitton’ Gehry building. Having just returned from three intense days at this museum, I found the building crowded and lacking in clear markings by which to link the in-phone acoustical guide (which was excellent) to the floor plan of the galleries. My preference is the Guggenheim Museum’s Gehry building in Bilbao Spain.