It’s been a while since my last View, which was A Primer on The American Rescue Plan. Since then, I have spent some time thinking about tobacco; and frankly, that’s a subject on which I have rarely, if ever, reflected. Then again, it’s not COVID, or its aftermath; and has nothing to do with the events of Jan. 6, 2021, or their aftermath.

To explain, Christina and I saw an excellent production of Say Goodnight, Gracie late last year at the venerable Ivoryton Playhouse with a CDC-compliant and COVID-cautious audience.

Goodnight is a one-man play based on comedian George Burns’ reminiscences of his life with Gracie Allen. George was usually seen with a cigar in hand, and it became one his trademarks; and a prop in the Ivoryton production. If your knowledge of vintage television extends no further back than Seinfeld, the Burns and Allen Show was broadcast from 1950 to 1958; and Burns used “Say goodnight, Gracie” as the sign-off at the end of each episode.

Moreover, the New York Times carried a story by Corey Kilgannon in mid-November regarding a group of Morehouse College students, who traveled from Atlanta in the early-1940s to earn money for tuition by working on tobacco farms in Connecticut’s Farmington River Valley. Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of those students; and, in January, the United States commemorated what would have been the civil rights leader’s 92nd birthday.

If you’ve read any of my past columns, you know that I enjoy reading history; and especially enjoy ferreting out what’s unique. All that said, I have never used any tobacco product.

My treatise on CT tobacco, which is presented in two parts, is not a review of the well-documented health risks associated with first- or second-hand tobacco smoke; but, ultimately, an historic review of how tobacco became a cash crop in Connecticut.

In doing my research, I was amazed at how often tobacco intersected the course of history.

I became acquainted with tobacco farming in the late-1970s while serving my active duty at a Naval Hospital in Southern Maryland. At the time, there were several large farms growing “sot weed”, as it’s also been called, in both Calvert and St Mary’s counties; much of it in the latter by Amish and Mennonite farmers, who grew it both as a market commodity and for personal use.

To provide some context for Part 2, which explores tobacco farming in CT, I am going to examine–albeit at a high level–the development of the international tobacco trade, beginning with the early voyages of the European explorers.

Discovery of Tobacco in the New World

Spanish and Portuguese explorers were introduced to Nicotiana tabacum in the late 15th and early 16th centuries by the indigenous peoples of the Americas and the Caribbean, who had already cultivated, consumed, and traded it for hundreds of years. The explorers returned to Europe with bales of tobacco and, more significantly, began large scale tobacco cultivation and export from their colonies in the New World.

Note that tobacco was unknown to Europe before those voyages.

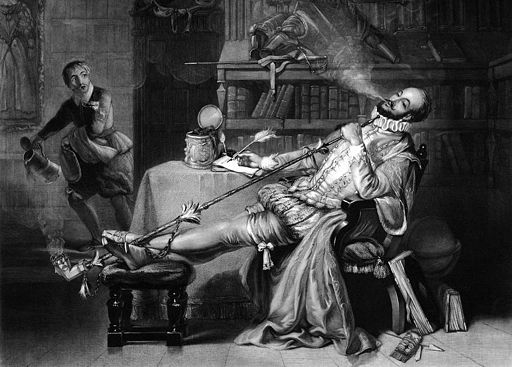

The English were probably first introduced to tobacco by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1586, on his return with the settlers rescued from the ill-fated Roanoke Island colony. However, it is likely that the use of tobacco had been passed onto British sailors by Spanish and Portuguese sailors well before the Roanoke rescue.

Sir Walter became an avid and influential advocate of tobacco, and many other English nobles then also indulged. He is said to have presented tobacco to Queen Elizabeth I; and, of course, smoking then became the rage in the Royal Court.

Recreational use of the addictive stimulant soon covered England and much of Europe in smoke; and, unfortunately, many believed that it had health benefits and that smoking cured all manner of illnesses, including gout, hysteria, and cancer; and when applied externally, could be used for bites from poisonous reptiles and insects, ringworm, and to increase the growth of hair.

Pipe-smoking then grew rapidly across all levels of English society and the English demand for tobacco became the greatest in the Old World. One historian described it as a “insatiable.” Note that the use of cigarettes as the primary vehicle for consuming tobacco did not become commonplace until well after the Industrial Revolution.

However, the English had a serious problem — availability of tobacco. By the late 1500s, not a single English tobacco plantation existed in the New World, which meant that obtaining it relied on trade, smuggling, or capturing vessels bound for Portugal or Spain. This supply problem is cited by many historians as one of the precipitating factors in the decision to establish a permanent colony in the Americas.

King James I, in his 1604 “Counterblaste to Tobacco,” voiced his opposition to the “noxious weed” and his concern that tobacco smoking had serious social and health implications. He then raised the taxes on tobacco in an effort to reduce use.

The Tobacco Mystique

Despite the King’s “Counterblaste,” tobacco developed an “aura” amongst the “smoking public.” For example, the opening speech of Moliere’s Don Juan begins, “There is nothing like tobacco. It’s the passion of the virtuous man; and whoever lives without tobacco isn’t worthy of living.”

A century later, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle continued in that vein in The Red Headed League, wherein a contemplative Sherlock Holmes, while considering a complex problem, informed Dr. Watson that, “It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.”

Finally, in World War I, General John Pershing appealed from France: “You ask me what we need to win this war”; and I answer “tobacco, as much as bullets.”

The King Addresses England’s Tobacco Deficit

In 1606, King James I granted a charter to the Virginia Company of London to establish permanent colonial settlements in the New World. Although their primary motivation was the hope of reproducing the wealth and riches that the Spanish brought home after they looted the Aztec empire; the Company also supported the English national goals of offsetting the expansion of other European nations abroad, finding a sea passage through the New World to India and Asia, and converting the indigenous peoples to the Anglican religion.

Their journey began that December and in May,1607, three ships with over 100 male colonists and another 40 crew members arrived in the New World to start a settlement at Jamestown, which they named after their king.

Location, Location, Location

Jamestown was selected because its waters were deep enough to enable the English to secure their ships at the shoreline, its position was defensible, and there was no native inhabitation. The reasons for the latter quickly became obvious.

The settlement was on a mosquito-infested, swampy peninsula, downstream from nearly 15,000 native Algonquians, who lived in more than 100 villages, and were ruled by a powerful leader, Powhatan (the “Powhatans.”)

Immediate Problems

The settlers arrived without sufficient food supplies and an inadequate group of skilled farmers, skilled tradesmen, and laborers. Their group included a large number of wealthy members of the gentry, whose background did not include much manual labor.

Their water source was brackish and unsanitary, and they developed typhoid and dysentery. Worse still, mosquitoes in the marsh carried malaria. Their governing council, which was proscribed by the king, lacked authority and was ineffective.

They had landed during a prolonged drought, which made finding fresh water and planting any crops at all very difficult.

Relations with the Powhatans, whose harvests were also impacted by the drought, were tenuous; and degraded into open conflict, as the English, who were forced to rely on them for most of their food; eventually escalated from trade, to raiding the smaller villages.

By the end of 1607, Jamestown was close to failing, and only the periodic arrival of supply ships from England held the colony together.

At this point, I am going to change tack from this play-by-play analysis of the trials and tribulations of the settlers, and discuss the activities of some key people who made the venture succeed (spoiler).

Captain Christopher Newport

Newport was an English seaman and privateer, who was captain of the largest of the three ships that carried the earliest settlers to Jamestown; and in overall command of the convoy on that first voyage. He also made several supply trips between England and Jamestown, which, as noted above, “held the colony together.”

In 1609, he became Captain of the Company’s newly launched “Sea Venture,” which was the flagship of a new larger convoy carrying settlers, provisions, and the first group of government officials to Jamestown. On that voyage, the “Sea Venture” sailed into a fierce storm, ran aground, and was forced to temporarily land in Bermuda to make repairs.

Captain John Smith

Smith became the colony’s leader in 1608, the fourth in a succession of council leaders. His administration had the advantage of the King’s second charter, which created a much stronger form of governance under the now “Governor” John Smith, and included a period of military law that carried harsh punishments for those who did not obey.

Smith quickly instituted the policy: “He that will not work, will not eat.” Unfortunately, he was injured in late-1609 and returned to England. His departure was followed by a period of warfare with the Powhatans and the deaths of many settlers from starvation and disease.

John Rolfe

Rolfe arrived in Jamestown in 1610 with the “Sea Venture” convoy along with 150 other settlers. He began cultivating tobacco, using seeds from Trinidad, or the West Indies, and began development of Virginia’s first profitable export. Note that how Rolfe came by the tobacco seed is not known.

In 1614, Rolfe married Powhatan’s daughter, Pocahontas. The couple traveled to London in 1616 with their infant son Thomas, with the expectation of stimulating investment in the Jamestown settlement. Pocahontas, who was christened Rebecca before the voyage, was presented to English society as an example of the “civilized savage.”

She died before returning to Virginia. Their marriage created a climate of peace between the colonists and the Powhatans; which continued for eight years as the “Peace of Pocahontas.”

Virginia Tobacco was an Unqualified Success

Rolfe’s new and milder tobacco proved immensely popular in England, helping to break the Spanish monopoly and creating a stable economy for the colony.

By 1617, the colony was exporting 20,000 pounds of tobacco annually; doubling that amount in the following year. Historian Lee Pelham Cotton estimates that by 1640, London was importing nearly a million and a half pounds of tobacco per annum from Virginia.

James I’s “noxious weed” had become the economic staple of Virginia; and would ensure the survival of the colony. By the beginning of the 17th century, the Virginia Colony became the wealthiest and most populated British colony in North America, which was probably the impetus for commissioning further settlements in the New World.

Indentured Servitude and Slavery

From the beginning (i.e., about 1500), the Portuguese had enslaved the indigenous natives in their colony of Brazil to work on their sugar cane, cocoa, and tobacco plantations The import of African slaves began mid-16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries.

The British hesitated to establish slavery in Virginia because they relied on indentured servants for the grueling labor in the tobacco fields. However, the growing demand for Rolfe’s tobacco resulted in a huge need for more field laborers; and, unfortunately, coincided with declining numbers of indentured servants willing to emigrate from England. The number of slaves increased significantly thereafter.

Author’s Notes:

In Part 2, I will review the expansion of English settlements into New England, with particular focus on how tobacco developed as a cash crop in Connecticut.

I will also consider Martin Luther King, Jr.’s experience in the early-1940s as a college student “working tobacco” in the Farmington River Valley.

I will present the literature and the cinema that romanticized Connecticut tobacco; and finally, contrast the 1998 Tobacco Settlement with the more recent Opioids Settlement

However, before I close this essay, I wish to share my opinion that Disney got it all wrong.

The 1995 production of “Pocahontas” tells the story of Captain John Smith’s romance with Pocahontas, which progresses, much to the disapproval of her father, Chief Powhatan. Smith’s fellow Englishmen plan to rob the Native Americans of their gold. As the story continues, her father tried to execute Smith by clubbing him to death. Pocahontas prevented the bloody killing by resting her own head on his.

Of course, I could not corroborate any of this; but, refer you to the section above on John Rolfe.

What’s troubling is that, given Disney’s probable incorrect review of history, it may also be possible that Davy Crockett was not the “King of the Wild Frontier.”

Editor’s Note: i) This is the opinion of Thomas D. Gotowka.

ii) The photo published above of George Burns is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in the United States between 1927 and 1977, inclusive, without a copyright notice.

iii) The photo published above of Sir Walter Raleigh is available from the New York Public Library’s Digital Library under the digital ID 1107712: digitalgallery.nypl.org→digitalcollections.nypl.org. {{PD-US}}

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK. A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.