OLD LYME — The Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, presents Revisiting America: The Prints of Currier & Ives, on view through Jan. 23, 2022.

Currier & Ives was a prolific printmaking firm based in New York City in the 19th century. Founded by Nathaniel Currier in 1834 and expanded by partner James Merritt Ives in 1856, the firm produced millions of affordable copies of over 7,000 lithographs, gaining it the title, “the Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints.”

Revisiting America comes from the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, boasting a collection of nearly 600 Currier & Ives prints donated by Conagra Brands. Currier & Ives perpetuated Victorian ideals in its depictions of family, history, politics, and urban and suburban life—concepts that persist today partly as a result of the wide distribution of their images.

Revisiting America offers an opportunity for viewers to contemplate the complexities and contradictions of America’s past. For many people, what could be more iconic representations of America than the prints of Currier & Ives? For others, they are reminders of harmful stereotypes of the poor and indigenous and enslaved peoples. While a trip down America’s memory lane, the exhibition offers an opportunity to delve into the reality that the company’s romanticized scenes sometimes prioritized marketability over morality.

For the presentation at the Florence Griswold Museum, Curator Amy Kurtz Lansing expands upon the exhibition’s original scholarship with a section discussing artist Frances Flora Bond Palmer, examples of how Currier & Ives images were re-discovered and used in the 20th century, an explanation of lithography, and additions pertaining to the Griswold family.

Made to Sell

Currier & Ives prints were first and foremost commodities, with subjects often determined by popularity and sales figures.

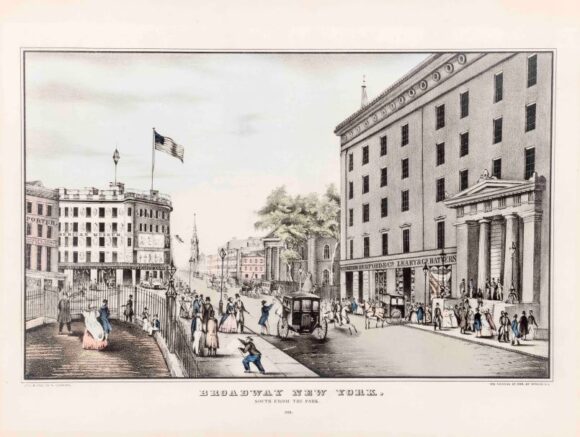

The choices the company made about what not to include in their images are as significant as what is depicted. For instance, although cities were often characterized by deep poverty and inequality, and perceived as full of crime, the firm’s views of urban streets represent an idealized version of the city—populated by fashionable, well-to-do people, clean thoroughfares, and regal buildings.

These idealized images appealed to rural and urban customers alike by offering visions of city life unaffected by the social and economic issues of the day. Broadway New York depicts the intersection of Broadway and Ann Streets in Manhattan. Once a quiet residential district surrounding City Hall Park, where people stroll in the foreground, the area became a bustling commercial and entertainment hub around 1841.

As author James Dawson Burn described, “There you may see the lean lanky Puritan from the east, with keen eye and demure aspect, rubbing shoulders with a coloured [sic] dandy, whose ebony fingers are hooped in gold.” The Currier & Ives print shows a bustling urban space with chic (but not diverse) passersby.

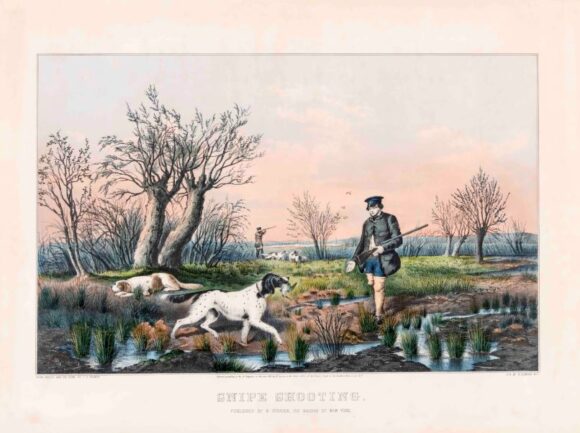

Other popular sellers were depictions of leisure time activities. The age of industrialization allowed Americans more opportunity to fill their day with sports and other pastimes. Popular hobbies of the time included hunting, fishing, and horse racing, topics marketed to men for their offices, saloons, and clubs.

Currier & Ives produced more than 750 prints related to horses and horse racing, such as Harry Bassett and Longfellow, in their Great Races at Long Branch, N.J. July, 2nd and Saratoga, N.Y. July, 16th 1872. The lithograph depicts two famous racehorses, Harry Bassett and Longfellow, whose two newsworthy races are memorialized in the text of the print.

The Social Media of the Day?

The sheer reach of Currier & Ives prints, sold in their New York City store, or by mail order, pushcart vendors, and far-flung agents, put their pictures in view of countless Americans, particularly women to whom they were marketed as affordable domestic decor.

The visually-based culture we live in today, with images circulating on the internet and social media, has its origins in the mass communications created in part by Currier & Ives. The prints promoted an optimistic ideal of home, family, and stability in their day, and continue to exemplify that view for Americans, who became acquainted with them in the 20th and 21st centuries, when we play out those same fantasies on our social media feeds.

A Griswold Connection

Nineteenth-century Americans took pride in the technological advancements being made across their nation. A rapid and wide-reaching revolution in transportation led the country from majestic clipper ships to powerful steam-driven boats and locomotives in a matter of decades.

At their height in the middle of the century, clipper ships—three-masted merchant ships designed for speed—ruled the seas and allowed for the faster-than-ever transportation of goods and people across the Atlantic and along the coasts.

Pairing Charles Parsons’s oil painting Clipper Ship Challenge at Griswold’s Wharf, Pine Street, New York (ca. 1851), on loan from local collectors, with James E. Butterworth’s Currier & Ives lithograph Clipper Ship Flying Cloud, (1852), Curator Amy Kurtz Lansing makes a Connecticut connection to the pursuit of global trade.

As captain of a fast sailing ship Florence Griswold’s father transported goods and people across the Atlantic until his retirement, while extended family members Nathaniel and George Griswold (owners of Challenge) imported tea from China.

Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1876)

Most of Currier & Ives’s artists are unidentified, their works published under the name of the firm rather than their own signature. However, one of their most prolific contributors, responsible for at least 200 lithographs, was Frances (Fanny) Palmer. Born and educated as an artist in England, Palmer and her printer husband owned their own firm before immigrating to America in 1844.

For Snipe Shooting (1852), the artist sketched the image from nature and made the final drawing on the lithographic stone. The image was printed with two separate inkings of the stone in different colors. Palmer’s artistic skill, knowledge of lithographic techniques, and ability to compose what became some of their most iconic prints gave Currier & Ives its edge over the competition.

Lithography Explained

Derived from the Greek for “writing on stone,” lithography was invented in 1796 by the German Alois Senefelder. It differs from other forms of image reproduction in the way it allows artists to draw expressively and with varying thicknesses of line right on the printing surface. Unlike etched or engraved metal plates that wear down over time, lithography allowed for printing many more copies, leading to its quick embrace by the industry in America by the 1830s.

By displaying lithography tools, including examples of stones used by artists today borrowed from neighboring Lyme Academy of Fine Arts, visitors better understand the process necessary to produce this type of print.

The Legacy of Currier & Ives

Why are Currier & Ives lithographs still so well-known today?

By the time Currier & Ives ceased operations in 1907 it had dispersed countless prints around the country. Hanging in homes, offices, bar rooms, clubs, and schools, these “engravings for the people” were often the only visual representations in Americans’ lives. After World War I, artists and collectors, striving to define an identity proudly distinct from Europe, delved into America’s past, where they re-discovered Currier & Ives. Suddenly appreciated again, newspapers in the 1920s published stories about the frenzied search for the prints in attics and shadowy corners, and noted their inclusion in art exhibitions.

Currier & Ives prints began to be reproduced on Christmas cards, collectibles, stamps, everyday dishes, and glassware. Examples of these items are on display. Connecticut artist George Henry Durrie, whose snowy views of country homes appeared in nearly a dozen Currier & Ives lithographs, are the among the most commonly reproduced as evocations of Thanksgiving and Christmas. Visitors to the exhibition have enjoyed sharing their memories through social media and interaction with staff, such as this quote from the comment book, “My wonderful grandfather gave cards at Christmas with Currier & Ives pictures on the front. I am 67 years old and still have some of them. Nice memory!” In Connecticut, Travelers Insurance included Currier & Ives images on their annual calendar in beginning in 1936 and encouraged the prints to become lasting décor with instruction

Collection

Roy King, a private collector from New York, assembled the extensive Currier & Ives print collection over a period of three decades starting in the 1950s. He collected 672 lithographs, most of which were purchased individually.

In 1975, King sold his prints to New York holding company, Esmark. The collection was kept together and shown across the country at universities and museums. Esmark allowed the prints to be seen in over 100 galleries, museums, and universities as well as two dozen other countries, created a wider audience than ever before for these popular depictions of quintessential American life.

The prints were then purchased by Conagra Brands, which installed them in spaces that were open to the public in Omaha, Neb. I

n June 2016, Conagra Brands donated the collected to the Joslyn Art Museum, where it could remain a cherished presence in the Omaha community.

Florence Griswold Museum

The consistent recipient of a Trip Advisor Certificate of Excellence, the Florence Griswold Museum has been called a “Giverny in Connecticut” by the Wall Street Journal, and a “must-see” by the Boston Globe.

In addition to the restored Florence Griswold House, the Museum features a gallery for changing art exhibitions, education and landscape centers, a restored artist’s studio, 12 acres along the Lieutenant River, and extensive gardens and nature trail. The Museum is located at 96 Lyme Street, Old Lyme, CT.

Visit FlorenceGriswoldMuseum.