This has been an unusual summer. Christina and I have been very “COVID – cautious” and, of course, fully vaccinated. We’ve postponed or canceled trips, missed Brimfield, both May and July, and probably Sept. And so, I retreated to my secure baseball space, and drafted this essay. There’s a lot of baseball jargon here.

In 2019, LymeLine published a series of essays on baseball; the final essay was published a few months before America’s first COVID case was identified in Washington state.

Inevitably, as the United States became consumed by COVID, Major League Baseball (MLB) curtailed its 2020 season; not reopening until late this past spring, albeit with restrictions (e.g., no spitting (really!), masks in dugouts, reduced crowd size, and some controls on snack and beverage sales).

Then, in mid-June, after 20 baseball clubs reached MLB’s 85 percent vaccination target, some protocols were loosened; e.g., all fully vaccinated players and staff may stop wearing masks in dugouts, bullpens, and clubhouses.

Nonetheless, in mid-July, the Colorado Rockies experienced a burst of COVID on their roster; and a Yankees v. Red Sox game was cancelled, not by weather, but because there was concern about a COVID outbreak on the Yankees.

Arguably the greatest rivalry in MLB, the century old Red Sox – Yankees conflict coincidentally began at the end of the 1918 influenza pandemic, and was actually connected to the first Broadway production of “No, No, Nannette”. Red Sox owner and theatrical producer, Harry Frazee, used the proceeds from the sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees to help finance several Broadway productions, including the aforementioned “No, No,”. Tickets for the games are handed down in families

If you are one of the few New Englanders unfamiliar with the impact of that sale, I recommend Dan Shaughnessy’s The Curse of the Bambino.

Some of America’s past sentiment for the sport was best expressed by James Earl Jones, who, as Terence Mann in Field of Dreams, said of baseball: “it’s a part of our past, and it reminds us of all that once was good and could be good again.” I know that my dad felt that way, and he passed some of it on to me. Note that the Mann character was actually J. D. Salinger in the novel, Shoeless Joe, which was adapted for the movie.

The “Phenom”:

My inspiration to extend the 2019 series into an extra inning really came from some highlights of a Red Sox loss to the Angels, during which the reporter described an Angels’ player, Shohei Ohtani, as MLB’s new “phenom”, which is sportscaster jargon for a player with phenomenal ability.

Sports Illustrated described Ohtani as a “once-in-a-century player; a ballplayer in the most fundamental sense of the word. He pitches, hits and runs, and does all of it with the irrepressible joy and purpose of a Little Leaguer.”

So, despite the hyperbole, he does have a 100 mph fastball, and was selected as both a starting pitcher and designated hitter for the All–Star Game on July 13th. He’s currently the American League home run leader, and the first player in MLB history to have (both) 37 homeruns and 15 stolen bases by the end of July.

MLB’s Dependence on international players:

It is ironic that this essay’s title is derived from a Walt Whitman piece, who, as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in the mid-1840s, wrote: “I see great things in baseball. It’s our game, – the American game.”

In 2018, Forbes Magazine reported that nearly 30 percent of active players are foreign born (and increasing). Five Latin American countries have consistently provided the largest portion of these players; including the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Cuba, the Puerto Rico territory, and Mexico.

Contributing Factors:

MLB began an expansion in 1961 that eventually increased the number of teams from 16 to 30; and, at the same time, began to eliminate affiliations with many of their minor league teams, which have always served for development of players not yet ready for play at the highest level.

Further, colleges and universities discovered the revenue potential of football and basketball, which may have also led to fewer athletic scholarships offered in baseball. Thus, MLB teams were compelled to look farther afield for talented players.

Noteworthy players born outside our borders:

Ohtani is not the first Japanese born MLB star. He is a successor to Ichiro Suzuki and Hideki Matsui, who were both outstanding players in Japan and the United States.

Players from the Latin American countries have had substantial influence on the game. The following includes profiles of a few recognizable players who have impacted the sport; selected only from the group of Latin players, who have already been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Puerto Rico native, Roberto Clemente, played 18 seasons (1955 –) for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He played in 15 All-Star games, was National League MVP in 1966, the batting leader in four seasons, and a Gold Glove Award winner (fielding) for 12 consecutive seasons. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973, shortly after he died in a plane crash, while on a humanitarian mission to Nicaragua, taking critical supplies to earthquake survivors. He was the first Caribbean and Latin American player to be so honored. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Dominican native, Juan Marichal, was a starting pitcher for the Giants, Red Sox, and Dodgers from the early 1960s through the mid-1970s (1960-). Considered one of the most intimidating pitchers of all time; in 1983, he became the first Dominican player to be elected to the Hall of Fame. He is also remembered by baseball historians as one of the epic heroes in the 1963 “Greatest Game Ever Pitched”, dueling with another future Hall of Famer, Warren Spahn, in a 16 inning 1 to nothing win.

Venezuelan native, Luis Aparicio, played shortstop for the White Sox, Orioles, and the Red Sox in a career that spanned 18 seasons (1956-). He was known for his exceptional defensive and base-stealing skills. He entered the Hall of Fame in 1984, the first Venezuelan to be so honored. He was nominated, in 1999, to the MLB All-Century Team (i.e., the 100 greatest players).

Panama native, Rod Carew, had immigrated at age 14 and joined his mother, in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan. He was not a homerun hitter, although he is considered one of the greatest hitters of all time. He was known for his ability to make contact with the ball and get on base. He was selected for 18 All Star teams in his 19 seasons with the Twins and Angels (1967-). Of the baseball elite, only Ty Cobb, Tony Gwynn and Honus Wagner have more batting titles than he. He entered the Hall of Fame in 1991. Notably, Carew attributed his discipline as an athlete to his six years’ service in the USMC Reserve.

Cuban native, Tony Perez, recruited while working in a Cuban sugar factory, played 23 seasons at first and third base (1964 -), most notably as a key member of the Cincinnati Reds, who dominated baseball in the 1970sPerez was a team leader, and, during his career, accrued more than 2,700 hits, 379 home runs and two World Series championships. He entered the Hall of Fame in 2000.

Dominican native, Pedro Martinez, is considered one of MLB’s most dominant pitchers; with the highest winning percentage of any 200 game winner in the “modern era” (i.e., post WW2). In his 17 seasons (1992-), he played for five teams; most notably, for me, the Red Sox. He is a three-time Cy Young Award winner, and the only pitcher to compile over 3,000 career strikeouts in fewer than 3,000 innings pitched. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2015.

Although not yet in the Hall of Fame, I’ve added Mexican native Fernando Valenzuela to this list of notables. He pitched for six teams over 17 seasons (1981-), but was probably best known for his time with the Dodgers. He will be remembered for both his unusual windup and the “Fernando-mania” that accompanied him to games. He was an All Star in each of his first six seasons, and recorded an extraordinary five shutouts in his first eight starts as a major leaguer.

Cuban Baseball Pre- & Post-Revolution:

Cuba is important (in this essay) because it became the nidus for baseball development throughout Latin America.

Two Guillo brothers, who were educated at Spring Hill College in Mobile, returned to Cuba in the late 1860s with a ball and bat and an interest in bringing baseball to the island. They formed the Habana Baseball Club, and became one of three founding members of the Cuban League, which was formed in1878.

The Cubans took their sport to Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and the eastern coast of Mexico, which were also areas with some American influence.

Then, in 1898, the Spanish-American War expelled Spain from Cuba and provided opportunities for Cuban teams to play against teams touring from the United States. Note that Spain had opposed baseball and promoted bull-fighting.

The Cuban League admitted black players in 1900; and many of the best players from the American “Negro Leagues” were playing on integrated teams on the island, and Cuban players also played in the “Negro leagues”.

Professional baseball in the United States excluded the majority of Latin Americans because of their skin color, just as it barred African Americans.

Then, fueled by money from the sugar, tobacco and fruit industries, the Cuban League evolved into professional teams , who competed on the island and beyond its shores. There were also well-organized local amateur teams, comprised of workers from those industries.

Americans were introduced to Cuban baseball via the minor leagues: i.e., the “Havana Cubans” in the “Florida International League” (1946-53), and the “Cuban Sugar Kings”, in the higher-level International League (1954-1960).

Finally, Jackie Robinson broke the “color barrier” in 1947. and opened opportunities in the major leagues for non-white players. At that same time, the Cuban League entered into an agreement with MLB, and, as the “Cuban Winter League”, was used by them for player development and enabled recruitment of talented Cuban players.

On New Year’s Day, 1959, Cuban Dictator, Fulgencio Batista, was overthrown by revolutionaries led by Fidel Castro.

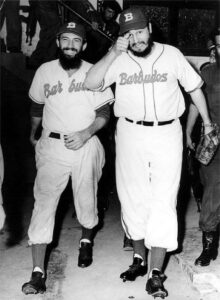

Hostile to the United States, who had backed Batista, U.S.-Cuba relations became strained; and Castro, a mediocre pitcher at the University of Havana who had no love for MLB; ended professional baseball in Cuba and forbade Cuban players from playing abroad. In 1961, Cuba replaced the professional system with new amateur baseball leagues. and organized the sport on a socialist model.

Castro’s view was that baseball, played by amateurs, was an important part of Cuba’s soul and identity. Consequently, baseball, almost by decree, became the Island’s national sport. His “Cuban National League” now includes 16 teams, comprised wholly of Cuban natives.

However, since these were all amateurs, supported by Castro’s socialist government, players were not paid very well. Baseball stars made less than $2,000 per year, and, of course, many defected to the United States. Castro acknowledged that “you cannot win if you have to compete against six million dollars with 3000 Cuban pesos.” He was correct, and the following are a few examples of what inspired Cuban baseball stars to defect.

- Rey Ordóñez defected in 1993 and signed a four-year $19 million contract with the Mets.

- Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez defected in 1997 and signed a four-year, $6.6 million contract with the Yankees.

- José Contreras defected in 2002 and signed a four-year $32 million contract with the Yankees.

- Jose Abreu defected in 2013 and signed a six-year $68 million contract with the White Sox.

Baseball is alive and well in Connecticut:

Southeastern Connecticut is home to several strong inter-scholastic programs. In addition, Babe Ruth teams in both Waterford and New London were competitive in the 2021 post- season tournaments; and, at a parade this past week, Efrain Dominguez, president New London’s City Council, said that “New London is a city of champions”; we’re here to honor and celebrate each other.”

Further, UConn finished the 2021 MLB Draft with five players selected, the most in the first 20 rounds of the draft since 2011.

Of special note, 2017 Hall of Fame inductee, Jeff Bagwell, was a standout on the soccer pitch at Xavier High School in Middletown, and still holds the school’s single-season scoring record. A multi-sport “phenom”, he was then “one of the most productive hitters in University of Hartford baseball history”; and left UHART as New England’s all-time leader in batting average and slugging percentage.

He was the Eastern League MVP in 1990, while playing for the minor league New Britain Red Sox.

Finally, he began his 15 seasons with the Houston Astros (1991-) as the “Rookie of the Year”, was selected unanimously, as league MVP in 1994, and hit 449 home runs over the course of his career. Some have compared his 1990 trade from the Red Sox organization to the Astros with the sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees in 1920. As some may recall, New Britain was a minor league team affiliated with the Boston Red Sox for much of the 1980’s through the early 1990’s.

Author’s Notes: I admit, this may be maudlin, but Roy Hobbs said it best: “God, I love baseball”. Regrettably, Americans may no longer claim that baseball is our national pastime. That distinction probably now belongs to both Japan and Cuba. At present, most American sports fans might say that football, especially NFL football, is our national pastime.

I said earlier that this essay was inspired by a sports reporter, who described Shohei Ohtani, as MLB’s new “phenom”.

Baseball was first introduced to Japan in 1872 by an American educator, Horace Wilson, who was there to assist in the modernization of the Japanese education system. The first professional competition occurred in the 1920s, and there are now two “major” leagues in operation; i.e., the Central and the Pacific Leagues, each with six teams.

However, high school baseball is particularly strong in Japan, with an amazingly ardent fanbase and a solid public image; perhaps like college football and basketball in the United States.

Japan’s national high school baseball championship is held each August over two weeks, with crowds approaching 50,000 per game, and broadcast live nationwide.

In closing, I have always felt that a classic 4-6-3 double-play is baseball ballet; Here’s one of the best.

Ozzie jumps over runner to turn double play – Bing video

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Thomas D. Gotowka.

Tom Gotowka

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

It is great that the MLB has been able to play its 2022 season in a largely safe manner. All professional athletes should remember that they are often role models to young children and take that responsibility with great care. Other professional sports leagues have been more lax in their COVID rules. It would be great to see the beat professional athletes doing PSAs to help people get vaccinated and for major league teams to bench players who are not.

Also, I’m surprised you made it through your article without a Yogi Berra quote. “Love is the most important thing in the world, but baseball is pretty good, too.”

Commander: Your Mom was always concerned that “when you reached a fork in the road, you would just take it”.