In this essay, I posit that many works of contemporary folk and rock music are the natural successors of the epic poems of antiquity. In support of that hypothesis, I begin with a brief review of the epic genre; and then, discuss a few contemporary works that I feel meet the epic standard.

The Epic Poem:

An epic is a long, narrative poem that chronicles the extraordinary deeds and adventures of courageous men and women. The earliest epic poems generally had no discernible author, and were probably developed in the pre-literate era. Those epics were conveyed orally, usually in brief episodes, either to an audience, or to another storyteller. However, epics were also created by a clearly-identified author.

At the Mindszenty School, where I was a college prep student many years ago, we studied epic works of both sorts.

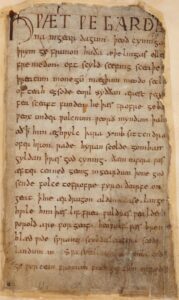

First page of Beowulf in Cotton Vitellius A. xv. Public domain.

“Beowulf” was written anonymously in old English, and set in the 6th century in what is now Denmark and Sweden. The hero, Beowulf, came to the aid of the Danish monarch, whose kingdom had been terrorized by the monster Grendel, who was notable as a descendent of Cain.

Although losing some of his warriors to Grendel, who then drank their blood; Beowulf finally slays the monster in a bloody encounter, and hangs the monster’s arm and claw over the rafters of the king’s great hall as proof of its death.

In a final act of heroism, Beowulf also kills Grendel’s avenging mother, though requiring a magic sword.

The “Odyssey,” which is a sequel to Homer’s “Iliad,” is a Greek epic poem, written near the end of the eighth century BC. The poem relates the activities of Odysseus, the hero, during the final year of the siege of Troy, and his 10-year, and epically perilous, journey home to Ithaca, after Troy’s fall.

We also considered Milton’s 17th Century “Paradise Lost,” but, absent a monster, and temptations from three sirens, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden drew only limited interest.

Clearly, the most noteworthy characteristic of an epic poem is its length. The “Odyssey” has 15,000 lines., “Paradise” over 10,000. Further, the epic hero (or heroine) is a great warrior, and willing to engage in intense combat.

In the following compositions, the title is followed by the author’s name and the publication date. A second name, when included, is, in my opinion, the best cover artist. A single name and date indicate that the author also performed the work.

I provide context for each work, and include abridged lyrics. I took care in my abridgement to ensure that the song’s sense and message remained clear. The original lyrics, in their entirety, are available on the internet.

I’ve included a song by Woodie Guthrie (see number III below), who is considered one of the most influential figures in American folk music. School children are often introduced to Woodie with his song, “This Land is your Land”.

1. “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” — Gordon Lightfoot (1976)

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was an American freighter that, when launched in 1958, was the largest ship on the Great Lakes, nearly 800 ft. long and weighing more than 13,000 tons without cargo. She hauled iron ore from mines in Minnesota to iron works in ports on the Great Lakes.

The skipper, Captain Ernest McSorley, was very experienced, and well-respected by his contemporaries and his crew. The ship sank on Nov. 10, 1975 in a storm on Lake Superior, with the loss of the entire crew of 29 men. The bodies were not recovered.

In true epic poem style, one of the prevailing theories regarding its sinking is that it was hit by a series of three consecutive “rogue” waves, a phenomenon called “Three Sisters” on Lake Superior. Their tendency to occur without warning, and with huge force makes them especially dangerous.

Gordon Lightfoot’s lyrics are a “play-by-play” of the disaster. Be sure to note the cook’s role in the progression of events.

Abridged Lyrics:

The legend lives on, from the Chippewa on down; of the big lake they call ‘Gitchee Gumee’.

Superior, it’s said, never gives up her dead, when the skies of November turn gloomy.

With a load of iron ore, twenty-six thousand tons more,

than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty.

That good ship and crew, was a bone to be chewed,

when the gales of November came early.

The ship was the pride of the American side,

when they left fully loaded for Cleveland.

The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait,

when the gales of November came slashing.

When suppertime came, the cook came up top;

saying, ‘fellas, it’s too rough to feed you’.

At seven p.m., a main hatchway caved in;

and he said, ‘fellas, it’s been good to know you’.

The captain wired shore that ‘he had water coming in;

and the good ship and crew were in peril’.

Later that night, when her lights went out of sight,

came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

And a church bell chimed, until it rang twenty-nine times;

for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald.

2. “Charlie and the MTA” — Steiner and Hawes, (1949) / The Kingston Trio

The song was originally composed for a “left-wing” mayoral campaign in Boston’s 1949 election, to protest the five-cent fare increase by the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). Fighting the fare increase was an important plank of the Progressive Party candidate, Walter A. O’Brien Jr.’s platform. He had also advocated the removal of the complicated entry/exit fare structure, and opposed the tax-funded bailout of the system’s previous operator.

O’Brien’s campaign had no funds for radio advertising, so he commissioned campaign songs from local folk artists, covering his themes; and played recordings from a loudspeaker on a truck driven throughout Boston.

The 1949 mayoral election was a raucous affair, with five candidates, including the amazingly popular, and notoriously corrupt incumbent, James Michael Curley, whose campaign song began, “Vote early and often for Curley”.

O’Brien finished last; and was routed by John B. Hynes, who then remained Mayor of Boston until 1960. Bostonians also approved a change in the structure of future mayoral contests (i.e., select two final candidates in advance of each general election).

Abridged Lyrics:

Well, let me tell you the story of a man named Charlie, who on a tragic and fateful day;

put ten cents in his pocket, kissed his wife and family, and went to ride on the MTA.

Well, did he ever return? No, he never returned; and his fate is still unknown.

He may ride forever ‘neath the streets of Boston; he’s the man who never returned.

Charlie handed in his dime at the Kendall Square Station,

and he changed for Jamaica Plain.

When he got there, the conductor said, ‘one more nickel’;

Charlie couldn’t get off of that train.

Now, all night long Charlie rides through the stations, crying, ‘what will become of me’?

‘How can I afford to see my sister in Chelsea or my cousin in Roxbury?’

Charlie’s wife goes down to the Sculley Square Station every day at quarter past two,

And through the open window she hands Charlie a sandwich as the train comes rumbling through.

The Kingston Trio’s original version of the song began with a spoken introduction: “The people of Boston have rallied bravely whenever the rights of men have been threatened. Today, the MTA, is attempting to levy a burdensome tax. Citizens, hear me out! This could happen to you.”

In 2004, the “Charlie Card” was introduced as the payment method for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA).

3. “Deportee — Woody Guthrie (1948) / Joan Baez

Guthrie said that the inspiration for “Deportee” was the radio and newspaper coverage of the Los Gatos Canyon plane crash, which provided the names of the flight crew and the security guard, but not the farm workers, who were also on the flight; referring to them only as “deportees.”

The crash resulted in the deaths of 28 migrant farm workers, who were being transported back to Mexico at the end of their braceros contract. The bodies of the migrants were placed in a mass grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno, Calif. The grave was marked only, “Mexican Nationals.”

The Bracero Agreement:

During World War II, the United States negotiated a series of treaties with the Mexican government to recruit Mexican seasonal workers, all men and without their families, to work on short-term contracts on farms and in other war industries (braceros.)

The program was developed because of severe labor shortages caused by the war. The labor contractors were expected to provide transportation to and from the Mexican border.

The first Mexican bracero workers were admitted in September, 1942, and by the program’s end in 1964, nearly 4.6 million Mexican citizens had been hired to work in the United States, mainly on farms in Texas, Calif., and the Pacific Northwest.

Abridged Lyrics:

The crops are all in and the peaches are rotting;

the oranges are piled in their creosote dumps.

They’re flying you back to the Mexico border,

to pay all your money to wade back again.

Some of us illegal, and others not wanted,

our work contract’s out and we have to move on.

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita;

adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria.

you won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane;

all they will call you will be ‘deportees’.

The sky plane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon;

a fireball of lightning, that shook all our hills.

Who are these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?

The radio says, ‘They are just deportees.’

Is this the best way we can grow our big orchards?

Is this the best way we can grow our good fruit?

Author’s Notes: First, I want to acknowledge the persistence of Messrs. Jakubowski and Corsi, English faculty at the Mindszenty School, who never assigned required readings that were also available in “Classics Illustrated” comics.

It is ironic that the United States has not yet addressed, in a bipartisan and humanitarian manner, immigration from Mexico, especially because we welcomed millions as migrant workers during and after World War II, (described above in “The Bracero Agreement”).

Our policy seems to remain: “They chase us like outlaws, like rustlers, like thieves,” which is also a Guthrie lyric.

Even American television recognized braceros. You may recall a late 1950s, and early ‘60s television series, “The Real McCoys”, which included a character, Pepino, who, I now realize, was a bracero worker on the McCoy farm in the San Fernando Valley.

We all first heard the Ojibwe term: “Gitchee Gumee” in Longfellow’s 1855 epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha”.

If Madame Editor agrees, I will continue this “epic poems” theme in the next essay, where I consider contemporary epic poems of conflict.

Editor’s Note to Mr. Gotowka: She agrees.

This is the opinion of Thomas D. Gotowka.

Tom Gotowka

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

Please do continue this theme! I’m interested in the author’s perspective on why Odysseus was so close to getting home so many times, and how human frailty messed up the plan every time. Sort of like in that other classic tale, Gilligan’s Island. Fascinating article!