George Washington’s Birthday Edition

In August, 2022, the Lafayette Trail marker on Old Lyme’s South Green that commemorates a visit by General Lafayette to the McCurdy house in 1824 was unveiled.

The marker joins another on the Green that recognizes Old Lyme’s role in the women’s suffrage movement—American suffragist and activist Old Lyme resident, Katharine Ludington, was a founding member of the Old Lyme Equal Suffrage League, the last president of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, and the first New England director of the League of Women Voters. Her name is also on a plaque honoring the state’s suffrage leaders in the south corner of the Connecticut State Capitol building.

The marker was of some interest to me because I grew up in Fredonia, N.Y., which had a visit by Lafayette on June 4, 1825. The Leverett Barker mansion, which eventually became the community’s library and historic museum; was lit for his arrival with candles at each window; scorching a window sash. One could not be a regular patron of Fredonia’s public library without gaining some appreciation for Lafayette’s role in our War of Independence.

Fredonia held a ceremony on June 4, 2023 formally acknowledging the Town’s newly-installed Lafayette Trail marker on the grounds of the Darwin R. Barker Historical Museum.

This “View” is about Lafayette and the era and events that formed the foundation on which America’s values, continuing greatness, and world prominence was established.

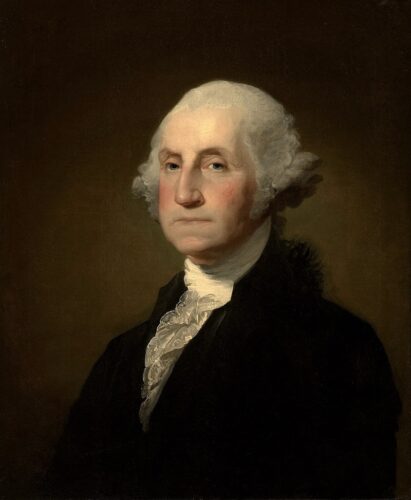

It is also appropriate to reflect on Lafayette as we acknowledge the anniversary of George Washington’s birth on February 22. (George Washington was born in Virginia on February 11, 1731, according to the then-used Julian calendar. In 1752, however, Britain and all its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar which moved Washington’s birthday a year and 11 days to February 22, 1732.)

I review General Lafayette’s life and important role in America’s War of Independence in this essay, and consider his first visit to Old Lyme in 1778; and then his remarkable “Farewell Tour” of the United States in the following “View;” but first, discuss the events that inspired the essay’s title.

On June 26, 1917, General John J. Pershing, the newly-appointed Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, and 14,000 United States infantry troops landed at the port of Saint Nazaire in France, shortly after the United States first entered World War I.

On that July 4th, Paris celebrated American Independence Day; and Pershing and a battalion of his troops made a symbolic march through Paris, ending in the Picpus Cemetery at the grave of the Marquis de Lafayette; where speeches were made at the tomb in tribute to Lafayette’s contribution to America’s War of Independence.

Pershing’s aide, Colonel Charles E. Stanton, provided the day’s most memorable speech: “America has joined forces with the allied powers, and what we have of blood and treasure are yours. It is with loving pride we drape the colors (i.e., the American flag) in a tribute of respect to this citizen of your great republic. And here and now, in the presence of the illustrious dead; we pledge our hearts and our honor in carrying this war to a successful issue. Lafayette, we are here!”

Terminology:

“Congress” refers to the Continental Congress, which served as the government of the 13 American colonies and later, the United States, from 1774 to 1789; proclaiming independence from Great Britain and its king in 1776 by adopting the Declaration of Independence. “Army” is the Continental Army of the United Colonies, and later, the United States, during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775 by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Congress; and created to coordinate the military efforts of the individual colonies and their militias under a single Commander in Chief, George Washington.

The Marquis:

Lafayette was a wealthy aristocrat, born into a family of noble French military lineage in 1757. He was christened Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, and commented in his autobiography that “I was baptized with the name of every conceivable saint who might offer me protection in battle.”

When he was two years old, his father perished in battle with the British during the Seven Years War. His mother and grandfather both died when he was twelve; and he inherited the title, great wealth, and extensive landholdings, making him one of the richest young men in France. At thirteen, he received his appointment to serve in the King’s Musketeers as a junior commissioned officer and began his education at the Military Academy at Versailles. Note that it was common for nobility to be given military ranks at a young age during this period in France. In 1773, and due to the influence of his future father-in-law (below); he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the prestigious Noailles Cavalry Regiment.

He married Adrienne de Noailles in 1774, the daughter of the Duc d’ Ayen. One of the most prominent and influential families in France; they had close ties to the British royal family.

Notably, he attended a dinner party in August, 1775 at which Great Britain’s Duke of Gloucester, the estranged younger brother of King George III, railed against his royal brother’s policies in the American colonies and praised the exploits of the Americans at the opening battles of the American Revolution at Lexington and Concord; which was later memorialized by Ralph Waldo Emerson in the “Concord Hymn” as “the shot heard round the world.”

Lafayette had found his cause. He and his friend and mentor, German-born French military leader, Baron Johann de Kalb, met with Silas Deane of Wethersfield, CT in December, 1776 in his role as the Continental Congress’ first envoy to France.

Congress had sent Deane to France to secure financial and military assistance and to investigate the possibility of a formal alliance.

He also promoted the American cause amongst French aristocrats and military officers; offering commissions to men who were willing to enter American service.

Deane promised Lafayette a commission as major general and the command of a division if he would travel to America; but also recruited the services of other foreign soldiers.

Deane negotiated a shipment of arms, munitions, and other supplies with the French that made possible an important victory at Saratoga in October, 1777. The battle was a turning point in the War and led the French to recognize the Colonies’ independence and continue their military assistance.

Note that Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee joined Silas Deane in Paris and the three were appointed by the Continental Congress as the diplomatic delegation to France. They worked together to negotiate a Treaty of Alliance and Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France, signed on February 6, 1778.

Lafayette was determined to join the War of Independence, perhaps even seeking to avenge his father’s death.

His wife was pregnant, and both King Louis XVI and his father-in-law opposed his decision. The King prohibited Lafayette’s departure, fearing that it would anger Britain.

Nevertheless, he and de Kalb sailed to the newly declared United States in 1777, seeking the commissions that had been granted by Silas Deane.

The General:

Following his safe arrival in Charleston, Lafayette spent a month traveling to Philadelphia, mostly on horseback; where he met with a Congress reluctant to promote him over more experienced colonial officers. He was not yet twenty years old and had no experience in combat. However, his willingness to serve without pay and his connections with the supportive French secured him his commission as major general on July 31, 1777.

He met with George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army at the City Tavern in Philadelphia.

Historian James R. Gaines reports that Washington was concerned about the teenage aristocrat’s ability to act in any command capacity. Lafayette’s arrival had been preceded by a series of disreputable men recruited by Silas Deane; and Lafayette was just, “The latest French major general foisted on him by the Congress.” Washington had been, “Trying to sweep back a tide of counts, chevaliers, and lesser foreign volunteers, many of whom brought with them enormous self-regard, little English and less interest in the American cause than in motives ranging from martial vanity to sheriff-dodging.”

Consequently, Lafayette served on Washington’s staff in Philadelphia for six weeks. Washington was taken by the young man’s ebullience and dedication to the American cause; and by the fact that he was a fellow Mason. Lafayette was in awe of the American Commander in Chief; and the two men formed a bond. In a matter of weeks, he was riding at Washington’s side on parade.

In September, Lafayette was put to the test in the Battle of Brandywine Creek, near Philadelphia. He fought with distinction on the front line and rallied the troops. Defeated by the overwhelming strength of the British army, he managed an orderly withdrawal of the Continental Army, despite his wounds; enabling them to safely retreat and reorganize.

His wounds at Brandywine incapacitated him for two months. Upon his return, he was given command of a division. Both he and de Kalb endured the hardships of the encampment at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777 -1778.

Lafayette fought with distinction in several skirmishes and battles with the British in the following years; and I present a few key milestones in the following.

Note that de Kalb was killed in action in 1780 at the Battle of Camden Court House in South Carolina.

Lafayette’s first visit to Old Lyme:

In late July, 1778.Lafayette stayed with John McCurdy whilst his troops were quartered on Old Lyme’s South Green, which was much larger then.

I draw from historian Katharine Mixer Abbott’s “Old Paths and Legends of the New England Border” in describing Lafayette’s brief stay. “Above stacked arms among shadowy elms on the green in Old Lyme waved the white fleur-de-lys, and our yearling stars and stripes. Major General Lafayette, in yellow satin waistcoat with the red and white trimmings of the blue coat fastened with gold buttons. Lafayette had ordered a night’s rest for Varnum’s and Glover’s brigades.”

Note that Varnum and Glover were not among the “lesser lights” of the Revolutionary War. General Varnum served at the battles of Red Bank, NJ in 1777 and the Battle of Rhode Island in 1778. He was also at Valley Forge.

General John Glover’s 14th Continental Regiment of Marblehead, Mass. comprised primarily of seamen, mariners, and fishermen, was a highly diverse brigade of volunteers who distinguished themselves in two crucial operations.

In August 1776, the Continental Army was soundly defeated at Brooklyn Heights and nearly trapped by the British army. In a surprise nighttime operation in the wind and teeming rain, Glover and his regiment ferried Washington’s 9,000 men, horses, artillery, and supplies across the East River to the relative safety of Manhattan; saving them from entrapment.

On Christmas night in 1776, Glover’s regiment ferried Washington’s army of 2,400 men, horses, and artillery across the Delaware River in a blinding snowstorm for a surprise attack on the morning of December 26, 1776 on 1,400 Hessian soldiers garrisoned at Trenton, NJ. Washington attacked, defeated the Hessian garrison, and turned the tide of the war.

Lafayette petitioned Washington to allow his return to France in February,1779 to work with American emissaries Benjamin Franklin and John Adams and negotiate additional troops and supplies with the government of Louis XVI,

He arrived back in America in April, 1780 with the news that the King had agreed to send French troops and relocate six ships of the line from the French fleet in the Caribbean in support of the Americans.

In July, General Rochambeau arrived near Newport, R.I. with an army of 5,300 infantry men and 450 officers to join the Continental Army and fight alongside Washington.

The following year, Lafayette was given independent command and sent to Virginia to conduct “hit and run” guerrilla actions against forces led by the traitor, Benedict Arnold; and then shadow the army of Cornwallis. Washington and Rochambeau marched their combined force south to Virginia and joined Lafayette’s troops on September 9th, entrapping British General Cornwallis’ 8,800 English, Hessian, and provincial troops.

Just before their arrival in Virginia, the French fleet under the command of Admiral de Grasse had encountered and defeated British Admiral Thomas Graves’ fleet near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay; preventing the Royal Navy from reinforcing or evacuating the British force.

War’s End:

The American Siege of Yorktown began on September 28 and ended on October 19, 1781 with the surrender of General Cornwallis. It was a crushing defeat for the British army, leading to the end of the war.

Yankee Doodle:

In the aftermath of the Siege, the surrendering British soldiers marched between the lines of American and French soldiers as their band played a melody called “The World Turned Upside Down;” but acknowledged only the French, refusing to pay the American soldiers any heed. Lafayette was outraged at the slight and ordered his band to play “Yankee Doodle” to taunt the British as they handed over their weapons and returned to Yorktown under militia guard. “Yankee Doodle,” originally embraced by the British military to mock their American counterparts, was named CT’s official state anthem in1978.

Note that music in the Continental Army consisted of fife and drum corps. It was used not only to boost morale, but also for communication and regimentation; and was included in his drill manual, “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States;” — aka, the “Blue Book,” that Baron von Steuben had drafted for George Washington in 1779.

Lafayette Square:

Monuments honoring Lafayette and Rochembeau and other Revolutionary War figures are located across from the White House in Lafayette Square. On June 1, 2020, amid the George Floyd protests in Washington, D.C., law enforcement officers, with orders from the Attorney General, used tear gas and other riot control tactics to forcefully clear peaceful protesters from Lafayette Square, creating a path for then-President Donald J. Trump and some senior administration officials to walk from the White House to St. John’s Episcopal Church; where Trump bizarrely held up a Bible and posed for a photo op. The methods used to clear the peaceful demonstrators from Lafayette Square were widely condemned as excessive and an affront to the First Amendment right to freedom of assembly.

Just before visiting the church, Trump had delivered a speech in which he urged state governors to control protests by using the National Guard to “dominate the streets,” or he would otherwise “deploy the United States military and quickly solve the problem.”

Note that the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 prohibits the use of U.S. military forces to perform the tasks of civilian law enforcement, unless explicitly authorized by Congress. However, the President, under his or her constitutional powers to put down insurrection, rebellion, or invasion may declare martial law when local law enforcement and court systems have ceased to function. The Act does not apply to the National Guard, when acting in a law enforcement capacity within its own state, and under orders from the governor of that state.

In closing, “May God bless America and may God protect our troops.”

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Thomas D. Gotowka.

Author’s Comments: i) It is always important to recall America’s history, especially as we move further into this important election year, as one candidate seems to misremember and /or misunderstand the values that have kept America great.

ii) I was amazed at the distances that troops moved during the period discussed above. As noted above, In my next “View,” I will cover Lafayette’s farewell tour of the then 24 states, of the United States, which began In 1824, at the invitation of President Monroe.

About the Author: Tom Gotowka is a resident of Old Lyme, whose entire adult career has been in healthcare. He will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK. A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

Sources:

Abbott, Katharine M. (1908) “Old Paths and Legends of the New England Border- The Eastern Coast.” G.P. Putnam & Sons. New York and London. 1908

American Battlefield Trust. “Winter at Valley Forge.” 09/21/2017

Daughan, G.C. “Fight Again Another Day.” History. 09/25/2017

Drury, D. “The Rise and Fall of Silas Deane, American Patriot.” Connecticut History. 10/02/2020.

Editors. “Lafayette arrives in South Carolina to serve alongside General Washington.” History. 11/13/2009.

Fischer, D. H. (2006) “Washington’s Crossing”. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gaines, J. R. (2007). “For Liberty and Glory: Washington, Lafayette, and Their Revolutions.” New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Gotowka, T. “A View from My Porch: The Marquis, Groucho, Sam, and Me” LymeLine. 02/19/2021.

Lafayette, M. J. P., “Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts of General Lafayette.”

Project Gutenberg eBooks. Released 06/01/2005

Leepson, M. “George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette.” The George Washington Presidential Library.

McNamara, Robert. “The Marquis de Lafayette’s Triumphant Tour of America.” ThoughtCo. 02/16/2021.

Obituary. “Katharine Ludington.” The Hartford Courant. Hartford, CT. 03/11/1953. p.14.

Observer Today. “New historical marker coming to Fredonia to honor Lafayette.” The Observer. 05/31/2023.

Old Lyme Historical Society. “The Lafayette Trail marker at the Old Lyme South Green was formally unveiled at the Old Lyme Town Band concert on Sunday.” Facebook. 08/09/2022.

Project Gutenberg eBooks. Released 06/01/2005.

Parker, A.A. (2010) “Recollections of General Lafayette on his Visit to the United States in 1824 and 1825; with the most remarkable incidents of his life, from his birth to the day of his death.”

Keene, N.H.: Sentinel printing company

Potter, B. “Lafayette Becomes a General, 1777.” History Highlights. 07/30/2018.

Powell, J. “Lafayette: Hero of Two Worlds.” Foundation for Economic Education. 09/01/1997.

New England Historical Society. “Lafayette Returns to America.” New England Historical Society.

Schellhammer, M. “The Daring Departure of Lafayette.” Journal of the American Revolution. 11/21/2013.

Wilde, R. “The Role of France in the American Revolutionary War.” ThoughtCo, 04/05/2023.