“But I digress …”

“But I digress …”

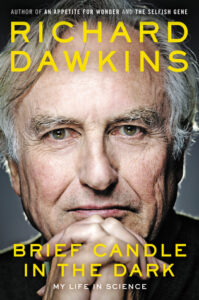

Ostensibly a continuation of his autobiography, this engrossing and superbly entertaining ramble by Dr. Dawkins, the noted Oxford zoologist, biologist, and humanist, stretches your knowledge and imagination. Is it possible to read an autobiography that is self-acknowledged as a, “Series of flashbacks, divided into themes, punctuated by digressions and anecdotes,” without losing your place, your mind and your direction?

Certainly!

And oh, those digressions: evidence of a perambulating and ever-curious mind. He drops names in his stories, recollections, and diversions, and it is fascination to follow his mind as it rambles over memory’s landscape, “… flitting like a butterfly as the interest takes me.”

Dawkins warns the reader early in his writing with a poem:

What is Life, if full of stress

We have no freedom to digress?

But if the prospect you enrages

You’d better skip the next few pages!

Neither is he reluctant to throw in a pun, trying to bridge the gap between literature and science, as in, “Où sont les C. P. Snow’s d’antan?” (a corruption of the question of one of France’s most famous poets Francois Villon’s question, Mais où sont les neiges d’antan?, which translates into English as the well-known line, “But where are the snows of yester-year?” taken from Villon’s poem Ballade des dames du temps jadis, which, in turn, roughly translates as, “Ballad of the Ladies of Times Gone By.” C.P. Snow refers to Charles Percy Snow, who was an acclaimed English novelist and physical chemist.)

Charles Darwin and natural selection lie at the core of his studies: ”Natural selection is a miserly economist, invisibly counting the pennies, the nuances of cost and benefit too subtle for us, the observing scientists, to notice,” and “gene survival” is our dominant “utility.”

Dawkins is also known for his acerbic reactions to religious dogma and beliefs, a member of a writing group that includes Bertrand Russell, Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, and Sam Harris. His conclusion: “I have tried but consistently failed to find anything in theology to be serious about. Yet he is equally candid about the ever-present “limitations of science.”

I’ve read his The Selfish Gene, The God Delusion, and The Greatest Show on Earth, and fully intend to continue to be challenged as well as enlightened by his words. His penultimate chapter, some 120 pages, is a review of the themes from his 12 books:

- Explaining the gene as a replicator and a vehicle

- Extending the phenotype

- Genes as a ‘gigantic colony of viruses,” both amicable and malevolent

- Survival requires avoiding “being too risk-averse” and being “too laid-back.”

- Using a “functional story” as a ‘powerful aid to memory.”

- The sonar of bats (Might he have suspected the global arrival of a coronavirus?)

- “Only changes have surprise value” and “information is a mathematically precise measure of ‘surprise’ “

- The “power of cumulative natural selection”

- A cooperative gene is most likely to survive.

- The “meme” (pronounced like “cream”) is the “new soup of human culture.”

- And religion: “We have taken on board a convention that religion is off-limits to criticism.,” something that Dawkins resists. We can and should teach about it but we should never indoctrinate children in any particular religious tradition.

Dr. Dawkins’ parting poem, which speaks volumes of the man and his mind, is:

Still time to gentle that good night.

Time to set the world alight.

Time, yet new rainbows to unweave,

Ere going on Eternity Leave.

Editor’s Note: ‘Brief Candle in the Dark’ by Richard Dawkins was published by HarperCollins, New York 2015.

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008).

A 20-year resident of Lyme, Conn., he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction, a subject which explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there.

For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farm Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings.

His late wife, Ann, was also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visited every summer.