Editor’s Note: This the third part of Thomas Gotowka’s series titled “Great Leaders and Great Speeches.’ The previous two parts can be found at these links:

A View from My Porch: Great Leaders and Great Speeches, Part 1

A View from My Porch: Great Leaders and Great Speeches, Part 2

Part 2 concluded with President Truman’s decision to use the atom bomb to bring the war with Japan to an end; which was “an awful responsibility that has come to us.” This essay continues with several events and associated speeches that illustrate the development and expansion of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Although discussed chronologically, they are not contiguous; and there may be several years between or amongst them.

This essay spans the period from Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech in 1946, through American “boots in the sands” of Cuba in 1961. As always, quotation marks delineate a passage taken directly from the text or transcript of a speech; and the essay includes my own, (and others’) analyses of the content.

This is not intended to be an historical “play-by-play”, but a consideration of the “look and feel” of the United States through a review of some of the key events of that tense Cold War period.

Some Jargon:

The Cold War was an ongoing and largely, but not always, political and rhetorical period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, and their respective allies. The Cold War began after the surrender of Nazi Germany; and continued as the uneasy wartime alliance between the United States and its allies, with the Soviet Union rapidly deteriorated.

The “Cold War” phrase first appeared in a 1945 essay in the London Tribune by George Orwell: “You and the Atomic Bomb,” wherein he expressed his grave concern about life in a troubled world with weapons capable of immense, and almost instantaneous, destruction.

The “Iron Curtain”:

On March 5, 1946, Winston Churchill gave a speech in Fulton, Missouri that is considered by many as the West’s earliest volley fired in Cold War hostilities. The now former Prime Minister was in Fulton to receive an honorary degree from tiny liberal arts Westminster College.

He began with some flattery directed at President Truman, who shared the dais. “The United States stands at the pinnacle of world power. It is a solemn moment for the American democracy; for with this primacy in power is also joined an awe-inspiring accountability to the future”.

He continued: “It is my duty to place before you certain facts about the present position in Europe; from Stettin in the Baltic, to Trieste in the Adriatic; an iron curtain has descended across the Continent; and behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe”. All these famous cities. and the populations around them, lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere; and are subject to Soviet influence and a very high measure of control from Moscow”.

His use of the term ”iron curtain” had profound symbolic meaning; and was also used, from then on, in the West, to refer to the Soviet Union and its allies; expressing, as was Churchill’s intent, that those living in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe were oppressed, and denied basic human liberties.

Ironically, Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, in one of his many “manifestos”, expressed similar concern in the German newspaper, Das Reich, (The Empire) in February 1945. about an iron curtain falling if Germany lost the war. The term only really became in common use after Churchill’s speech.

The Hydrogen Bomb Soap Opera:

On Jan. 30, 1950, President Truman announced the development of a “hydrogen bomb”, which would get a significant portion of its explosive energy from fusion, or the joining of atoms, rather than fission, the splitting of atoms. “I have directed the Atomic Energy Commission to continue its work on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen superbomb.” He continued, “Like all other work in the field of atomic weapons, it is being, and will be carried forward, on a basis consistent with the overall objectives of our program for peace and security.”

Opponents of development of the hydrogen bomb included J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project to develop the atom bomb. He and others argued that little would be accomplished except the acceleration of the arms race.

The United States accelerated its program to develop the thermonuclear bomb after the Soviet Union detonated an atomic bomb in Kazakhstan in September, 1949, and immediately eliminated the monopoly held by the United States on nuclear weapons

Then, and just weeks later, United States and British intelligence discovered that Klaus Fuchs, a German-born top-ranking scientist in the U.S. nuclear program, had spied for the Soviet Union, which meant that the Soviets knew everything that the Americans did about how to build a hydrogen bomb.

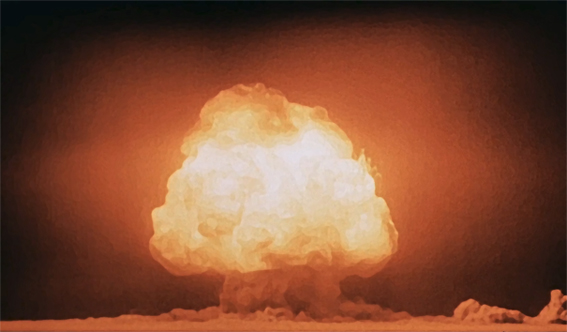

About two years later, the United States detonated the world’s first thermonuclear weapon, the 10.4-megaton “hydrogen bomb”, at Eniwetok Atoll in the South Pacific, vaporizing the island and leaving a crater more than a mile wide. The blast measured about 1,000 times stronger than the two atom bombs dropped on Japan ending World War II.

The detonation only gave the United States a brief advantage in the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union because, on Nov. 22, 1955, the Soviets detonated their first hydrogen bomb. The nuclear arms race, which became central to the Cold War, had taken a dreadful step forward.

Both America and Russia built up their stockpiles of nuclear weapons. By the late 1970s, seven nations had constructed hydrogen bombs.

“We Will Bury You”:

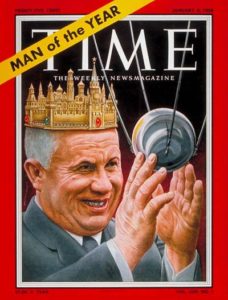

While addressing the ambassadors from ‘Western Bloc’ nations (i.e., a coalition of countries aligned with the United States) at the Polish Embassy in Moscow on Nov. 18, 1956, Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev declared, “It doesn’t depend on whether or not we exist. If you don’t like us, don’t accept our invitations, and don’t invite us to come to see you. Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you.”

The speech prompted the envoys in attendance from 12 NATO nations and Israel to leave the room.

“We will bury you” was interpreted as a threat by the Western press. Khrushchev attempted to “walk back” his threat in succeeding years.

While speaking to the National Press Club in Washington on Sept. 16, 1959, Khrushchev stated that “the words, ‘We will bury you,’ should not be taken literally; as is done by ordinary gravediggers who carry a spade and dig graves and bury the dead. What I had in mind was the outlook for the development of human society. Socialism will inevitably succeed capitalism.”

The “Military-industrial Complex”:

In a televised farewell to the American people on Tuesday evening, Jan. 17, 1961, President Eisenhower expressed his concern about the “acquisition of unwarranted influence by what he called “the military industrial complex” This address occurred just days before John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, where he challenged Americans to, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

Eisenhower’s remarks were especially noteworthy because he had served as Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces during WWII.

He urged his successors to balance a strong national defense with diplomacy in dealing with the Soviet Union. He was concerned about the emergence of a massive and permanent armaments industry; and warned that “the federal government’s collaboration with an alliance of military and industrial leaders, though necessary, is vulnerable to abuse of power”.

Eisenhower believed that the military-industrial complex tended to promote policies that might not be in the country’s best interest; and he specifically cited participation in the ongoing nuclear arms race.

The Bay of Pigs Debacle:

On Jan. 1, 1959, Fidel Castro drove his guerilla army into Havana and toppled the government of General Fulgencio Batista, a corrupt and despotic dictator, but an ally of American business interests.

Castro proceeded to reduce American influence on the island and nationalized the American-dominated sugar and mining industries. (At that time, American corporations and wealthy individuals owned more than half of Cuba’s sugar plantations.) He also encouraged other Latin American governments to act in a similar manner.

He established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union; and the United States, Cuba’s primary sugar importer, responded by prohibiting further import of Cuban sugar. However, the Soviets then agreed to buy the sugar and prevent the collapse of the Cuban economy.

This new order on the island (i.e., “Cuba Sí, Yanquis No”) made American officials very concerned about a potential threat less than 100 miles from our mainland; and the State Department and the CIA began to develop plans to remove Castro.

Consequently, President Eisenhower authorized the CIA, early in 1960, to train and equip a guerilla army of Cuban exiles that could serve as an invasion force that would overthrow the Castro regime.

President Kennedy, who was inaugurated on Jan. 20, 1961, inherited Eisenhower’s CIA campaign against Cuba. The new President is said to have had some initial doubts about the wisdom of the plan, and was uncertain whether Castro posed any real threat to the United States. He feared any “direct and overt intervention by the American military in Cuba”, which the Soviets would likely see as an act of war and be forced to retaliate.

So, he gave his support to the plan, but only if it appeared that the invasion was purely an internal matter of Cuba, and not linked to the United States. The CIA assured him that our involvement in the invasion would be “masked” and remain secret. The action would appear to have been initiated by Cuban dissidents and exiles; and would spark an anti-Castro uprising on the island. They promised him that the invasion would be both “clandestine and successful”.

By April, Kennedy was determined to make an example of Cuba to prevent the spread of communism in the West, and the resultant extension of Soviet influence. He firmly believed that the Cuban leader’s removal would demonstrate to Russia, China, and doubtful Americans that he was serious about winning the Cold War.

The Administration soon severed diplomatic relations with Cuba and accelerated invasion preparations. However, he raised his concern that the plan might be “too large to be clandestine. and too small to be successful”. The plan was intricate and complicated, and required that every phase work perfectly.

Nonetheless, on April 17, 1961, the CIA launched what they expected to be the definitive strike by “Brigade 2506”, the name given to the force of 1,400 American-trained Cuban exiles.

Unfortunately, the preliminary stages of the invasion were fraught with failure, and it was too late to apply the brakes. The Brigade was gravely outnumbered by Castro’s troops, who had them pinned on the beach. They surrendered after less than 24 hours of fighting. 114 were killed. and over 1,000 were taken prisoner.

This was a humiliating defeat for President Kennedy. The incident undermined his new Administration and set the stage for a difficult summit just two months later with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. The failed invasion also strengthened the position of Castro’s government, which began to openly proclaim its intention to adopt socialism and pursue closer ties with the Soviet Union.

Note that Kennedy put the blame squarely on the CIA and himself for going along with the ill-conceived plan. On April 20th, he addressed a high-level media gathering:

“The President of our great democracy, and the editors of such great newspapers, owe a common obligation to the people: an obligation to present the facts, to present them with candor, and to present them in perspective. It is with that obligation in mind that I have decided to discuss the recent events in Cuba. “It is clear that the forces of communism are not to be underestimated, in Cuba or anywhere else in the world. It is clear that this nation, in concert with all the free nations of this hemisphere, must take an even closer and more realistic look at the menace of external Communist intervention and domination in Cuba. We face a relentless struggle in every corner of the globe that goes far beyond the clash of armies or even nuclear armaments.”

He then went on to detail the Bay of Pigs disaster and the developing threat of Cuba’s alignment with the Soviet Union.

Of some historic note, E. Howard Hunt, the CIA operative behind the development of Brigade 2506, resurfaced later at the center of Watergate, as one of the leading members of Nixon’s Special Investigative Unit, also known as the “plumbers”; who were hired to dig up dirt on Nixon’s opponents or enemies. Hunt, G. Gordon Liddy, and a few other “plumbers” also plotted the Watergate burglaries and other clandestine operations.

Some Final Thoughts:

Many western observers were concerned with Churchill’s use of the “Iron Curtain” descriptor, as they still viewed Russia as a wartime ally; but the term became synonymous with the Cold War divisions in Europe, just as the Berlin Wall later became the physical symbol of that division. One wonders how Winston Churchill and the President of the United States chose to share the dais at tiny Westminster College to deliver a major policy speech.

Tension between the United States and the Soviet Union increased steadily after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion.

The next essay further considers Cold War activities in Cuba, the important “visuals of the Cold War. And the gradual “wind-down” of hostilities, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. God save the United States.”

Tom Gotowka

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

I hope we all are very appreciative of LymeLine’s and Mr. Gotowka’s efforts to help us all know about and respect historical events. “The past is prologue.” Few of us not in our 6th, 7th, 8th or 9th decades have sufficient appreciation for the lessons and events of the past and how knowledge of them can guide us in solving our current problems. Mr. Gotowka’s mention of FDR’s Four Freedoms reminds me that those very same Four Freedoms are actively and in real “today” time celebrated by an organization called the Roosevelt Institute (a “progressive” “think tank” formed to be a living embodiment of the principles and values of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt) that hold in alternating years Four Freedoms Awards ceremonies in the U.S. and in Europe granting awards to living individuals and organizations that best represent those principles and values. These are living, every-day heroes impacting our everyday lives.

But, perhaps even more relevant to our society’s issues today, is the speech FDR gave at his State of the Union address of January 11, 1944 in which he suggested a second “Bill of Rights” to the nation. In addition to the Four Freedoms critically essential to freedom and democracy here at home and around the world, especially today, the concepts and principles FDR espoused on the Second Bill of Rights would go a long way towards solving many of our deep divisions and socioeconomic issues plaguing our communities and nation. A quick “refresher” on the Second Bill of Rights can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Bill_of_Rights.

.

Thanks for your comment. The interactions between FDR and Winston Churchill reflects good leadership during a terrible time, but is great reading. Unfortunately, I can’t point to the same during this current crisis.