Nazi Aggression through “A Rain of Ruin from the Air” on Hiroshima

Part 1 ended with a review of Theodore Roosevelt’s extension of the Monroe Doctrine to enable the United States to exercise “international police power” in the Western Hemisphere. I continue my review of significant speeches with one of Winston Churchill’s wartime speeches.

As noted last time, my selection is based wholly on my judgment that the speech is notable, or an important contribution to history. These speeches are arranged chronologically, but they are not contiguous. A passage taken directly from the text or transcript of the speech is delineated by quotation marks. Otherwise, the essay includes my own (and others’) analyses of the content.

6. Winston Churchill “We Shall Fight on The Beaches”:

Churchill demonstrates the skills that able leaders display when speaking to their nation in times of crisis. This address to the House of Commons occurred on June 4, 1940, just after the rescue of the British Expeditionary Force from the coast at Dunkirk. “Beaches” is often cited as one of the defining speeches of World War II. At that time, France was falling to the Nazis, and the threat of an invasion of Britain seemed a near certainty; so much so that Hitler had given the plan of invasion the code name “Operation Sea Lion.”

Churchill addressed the House of Commons to reconfirm, despite the near disaster at Dunkirk, the goal of “victory, however long and hard the road may be”, that he had declared in his May 13, speech (see below).

“Beaches” was the second of three major speeches given during that period in 1940. The others are the “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat” speech of May 13, and the later “Finest Hour” speech of June 18.

The speech was also an appeal to the Americans, who were still watching the war from the sidelines. Churchill eloquently and honestly informed the British of what was facing them all: “Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo, and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end”.

“We shall fight in France; we shall fight on the seas and oceans; we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be.

We shall fight on the beaches; we shall fight on the landing grounds; we shall fight in the fields and in the streets. We shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. And even if this Island, or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle.”

He ended with a gesture to America: pleading that, “in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

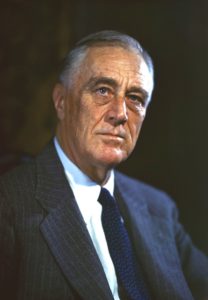

7. FDR’s Four Freedoms:

In his State of the Union Address on January 6, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to Churchill’s appeal and began to move the United States further away from its post-World War One policy of neutrality. He had watched with fear as Europe fell to the Nazis; and was intent on rallying public support for the United States to take an expanded role in the war beyond the Lend-Lease program that already permitted war supplies be sent to Britain.

He had already initiated a buildup of the military. “I find it, unhappily, necessary to report that the future and the safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders,” stating that, “the need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily – almost exclusively – to meeting the foreign peril”.

He noted that, “by an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to full support of all those resolute people everywhere who are resisting aggression and are thereby keeping war away from our hemisphere. By this support, we express our determination that the democratic cause shall prevail; and we strengthen the defense and the security of our own nation”.

He referenced his belief that America’s primary role was to support our allies as “the arsenal of democracy”, which he had introduced in a radio broadcast about a week before. “We cannot, and we will not, tell them that they must surrender, merely because of their present inability to pay for the weapons which we know they must have”. At that time, the United States was just nearing the end of the Great Depression, and industry, which had not yet recovered, was reluctant to expand.

The Defense Production Act was not enacted until 1950, at the start of the Korean War. However, Congress provided FDR with sweeping war powers, which he used to break through that reluctance. These powers ultimately enabled him to requisition supplies and property; and force entire industries to produce wartime products rather than products for civilians. America began producing airplanes, tanks, military vehicles, weapons, warships, and other defense-related products.

As justification, he stated that, “in the future, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms”. He insisted that “people in all nations of the world shared Americans’ entitlement to these same four freedoms: “the freedom of speech and expression, the freedom to worship God in his own way, freedom from want and freedom from fear”.

The value of FDR’s many “fireside chats”, which he began right after his first inauguration, should not be under-estimated in moving the nation’s industry into wartime production. His radio broadcasts of “conversations” with Americans were very “well-attended” (e.g., an estimated 60 million Americans listened to his first radio address), and he had gained the trust and respect of Americans, who had grown to appreciate his honesty and straightforward language.

8. President Truman and the Use of the Atom Bomb at Hiroshima:

Less than two weeks after being sworn in as President after FDR’s death, Harry S. Truman was briefed by Secretary of War Stimson on the top-secret Manhattan Project, which began in 1942 to develop an atom bomb. He was informed that “within four months, we shall, in all probability, have completed the most terrible weapon ever known in human history”.

After a successful test of the weapon, Truman formed the “Interim Committee” to “advise the president” on matters pertaining to the use of nuclear energy and weapons. The Committee’s first priority was to provide counsel on the use of the atomic bomb to bring war with Japan to an end.

The group considered four options: conventional bombing of Japan; ground invasion; demonstration of the bomb on an unpopulated area; and finally, use of the bomb in a populated or an industrialized area. Some historians have said that Truman and his advisers made the only decision they could have made in the context of finally bringing the war with Japan to an end.

Prolonging the war was not an option for the President. His decision to use the bomb was made to prevent the estimated one million casualties associated with a Normandy-type amphibious landing on the Japanese mainland. He believed that use of the bomb would also save Japanese lives, and wanted a swifter close to the war than any other option of force would provide.

Allied leaders had gathered in Potsdam, Germany, after the European phase of the war had ended; and before the final decision to use the bomb in Japan had been made.

Truman, Churchill, and Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek drafted a declaration that defined the terms for Japan’s surrender and made dire warnings if the country failed to end all hostilities. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was not part of the group because his country had not yet declared war on Japan.

Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945 (jointly with Great Britain, and China), demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan, and warning, otherwise, of “prompt and utter destruction.” The “Declaration” claimed that “unintelligent calculations” by Japan’s military advisers had brought the country to the “threshold of annihilation.”

Hopeful that the Japanese would “follow the path of reason,” the leaders outlined their terms of surrender, which included complete disarmament, allied occupation of certain areas, and the creation of a “responsible government.” It also promised that Japan would not “be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation.”

Japan did not acquiesce; and on Aug. 6, and 9, 1945, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed by dropping two atom bombs (known as “Little Boy”, and the more powerful “Fat Man”, respectively) At this time, the Soviet Union also declared war on Japan. On Aug. 15, Japan finally and officially surrendered.

On Aug. 6, 1945, President Truman delivered a radio address while returning home from the Potsdam Conference aboard the USS Augusta: “Sixteen hours ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT.

The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many-fold; and the end is not yet here.

“These bombs are now in production, and even more powerful forms are in development. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East”.

“By 1942, we knew that the Germans were working feverishly to find a way to add atomic energy to the other engines of war with which they hoped to enslave the world; but they failed”.

“The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us; as well as the battles of the air, land and sea”. We have now won the battle of the laboratories, as we have also won the other battles”.

“Scientific knowledge was pooled; and with American and British scientists working together we entered the race of discovery against the Germans”.

“We have spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history, and won. “What has been done is the greatest achievement of organized science in history”.

“We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum”.

“If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth”.

Some Final Thoughts:

President Truman’s decision to drop the bomb was very controversial. At the time, however, the majority of America’s political and military leaders believed that it was the best alternative. “It is an awful responsibility that has come to us.” He also recommended that Congress establish a commission to control the production and use of atomic power within the United States.

It is refreshing that, like many of his predecessors, and some of his successors, he believed that “the buck stops here”, and he accepted accountability for all the decisions of his administration. Truman valued scientists.

After FDR’s death, President Truman appointed former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt as a delegate to the United Nations, where she served as Head of the Human Rights Commission, and was instrumental in framing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the General Assembly in 1948. She often referred to FDR’s “Four Freedoms” when advocating for passage of the “Universal Declaration”.

I could have devoted this essay to the speeches of Winston Churchill, who exhibited the skills required of a wartime leader. Recordings of his speeches, are still available. I find his delivery to be very stirring.

Churchill, authored his own speeches, and used “repetition” very powerfully in “Beaches”, as did FDR in “Four Freedoms”; who repeatedly used the phrase “by an impressive expression of the public will” (in the full text.) JFK also did so in his “Berlin” speech, which is reviewed in a later essay.

I’ll wrap this up with an uncomfortable link to the WWII era. Repetition is, in no manner, synonymous with Joseph Goebbels’ Principles of Propaganda; which states, in part, that “if one wrong is reverberated many times, then people will accept that wrong as right”. “The most brilliant propagandist technique will yield no success unless one fundamental principle is borne in mind constantly; it must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over”.

With apologies, the alternative to Goebbels is Bob Dylan’s Principle: “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters.”

Part 3 begins with a speech that defines the advent of the “Iron Curtain”, considers the “Military- Industrial Complex”, and proceeds through the Cold War.

Tom Gotowka

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

thank you tom my whole family is enjoying your article agnes oconnor

Inspiring.

Thank you, Tom.

Mary Jo Nosal