Part 1: Washington’s Farewell through Theodore Roosevelt

I enjoy reading historic speeches. I often find them to be inspiring; and they can fill gaps in my understanding of an important event or period in history.

In this essay, I begin my review of these speeches, and provide some context for the events that precipitated their creation.

These essays will not be an exhaustive survey of the speaking arts. My selections are based solely on my judgment that the speech is notable, or makes an important contribution to history. A passage taken directly from the text or transcript of the speech is delineated by quotation marks. Otherwise, the essay includes my own, (and others’) analyses of the content.

These speeches are arranged chronologically, but they are not contiguous. They highlight leadership during periods of conflict and crisis.

There has been considerable argument in Congress in the past few years regarding “what the founders and framers really meant” when they drafted the principles passed on to us in the Constitution, So, I’ll begin with a review of the first president’s farewell to the nation.

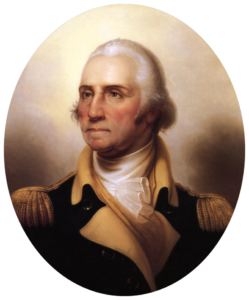

1. George Washington’s Farewell Address:

Washington wrote his “Address” near the end of his second term as president, working closely with Alexander Hamilton in the final draft. He also had input from James Madison; so, it represents the collective wisdom of some key players in the split from Great Britain and the founding of the United States. His “Address” was never presented as a speech, but was a public letter to the American people; and published in a Philadelphia newspaper, the American Daily Advertiser, on Sept. 19, 1796; and then, in newspapers throughout the country. His letter included three principles:

First, the importance of unity; “You have, in a common cause, fought and triumphed together. Your Union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear you to the preservation of the other”.

Second, he cautioned that “the worst enemy of government is loyalty to party over Nation”. Dominating regional loyalties could lead to factionalism and the development of competing political parties. He warned that, “if Americans voted according to party loyalty rather than the common interest of the nation, it could foster a spirit of revenge”, and “enable the rise of cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men who would usurp for themselves the reins of government”.

Third, he warned of the “danger of foreign entanglements” He believed that partisanship would open the door to “foreign influence and corruption.” He advocated that the United States be on good terms with all nations, especially in commercial relationships. “Inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded.” He believed that a foreign policy based on neutrality was the safest way to maintain national unity and stability.

2. Emerging American Foreign Policy – The Monroe Doctrine:

It became evident in the first quarter of the nineteenth century that European powers were trying to reassert their influence in the Americas. Russia had tried to expand eastward into Alaska, and Spain was establishing new colonies in Central and South America.

Consequently, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, on behalf of President James Monroe, began to articulate America’s foreign policy direction. In an address to the House of Representatives on July 4, 1821, Adams asserted that the United States is “the defender of freedom against the corruption of Europe, and should not let itself fall under the influence of any of those ‘old’ countries.”

“America, with the same voice which spoke herself into existence as a nation, proclaimed to mankind the inextinguishable rights of human nature, and the only lawful foundations of government.” “She has, invariably, though often fruitlessly, held forth to them the hand of honest friendship, and generous reciprocity.”

Two years hence, President Monroe proclaimed, in a Dec. 2,1823 Address to Congress, a new foreign policy initiative, largely drafted by Adams; that will always be known as the “Monroe Doctrine.”

This new policy forbade European interference in the American hemisphere, and also declared America’s neutrality in future European conflicts. It stated that “further efforts by any European nation to take control of any independent state in North or South America would be viewed as “the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States”.

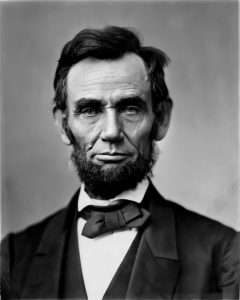

3. Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address:

Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865. The capital city was a mess at that time, with mud-soaked streets and over-flowing hospitals treating Civil War wounded. The event occurred at a time when victory over the Confederacy was imminent, and slavery in all of the United States was proclaimed “ended”.

Sherman completed his march through the south, and Grant was confronting Lee at Petersburg. There was concern that, because of the teeming rain, Lincoln would not be able to take the oath on the steps of the Capitol. However, the sun appeared as he rose to begin his speech.

In an account of the event in the New York Times, Walt Whitman “noticed that a curious little white cloud, the only one in that part of the sky; had appeared like a hovering bird, right over him.”

Lincoln did not speak of victory, but of sadness. He sought to avoid harsh treatment of the defeated rebels by reminding the thousands in attendance of how wrong both sides had been in imagining what lay before them when the war began. “Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war, rather than let it perish.”

Lincoln spoke of the unmistakable evil of slavery. “To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war. Neither party expected the magnitude or the duration that the war has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease” … (i.e., The Emancipation Proclamation).

He continued: “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continues until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword; and as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said; “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”… (Psalm 19:9)

Lincoln ended his inaugural address : “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass noted that the many African Americans in attendance, which included troops who marched in the inaugural parade, applauded vigorously, but were, “wonderfully quiet, earnest, and solemn during the speech.”

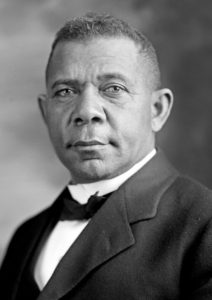

4. Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Compromise Speech:

B.T. Washington was born a slave in Virginia in 1856. After Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, he moved with his family to West Virginia, which had joined the Union during the Civil War as a free state.

As a young freeman, he worked his way as a janitor through Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University), and attended college at Wayland Seminary (which is now Virginia Union University). In 1881, he co-founded and became the first president and principal developer of what is now Tuskegee University.

He was advisor to several presidents, and the most influential spokesman for black Americans from the latter part of the nineteenth century through the first quarter of the twentieth century.

On Sept. 18, 1895, he gave a speech that would open the “Cotton States and International Exposition” in Atlanta. The “Atlanta Compromise” speech was the first address by an African American to a racially-mixed audience in the South. He asserted that vocational education, which gave black Americans an opportunity for economic security, was more valuable to them than social advantages, higher education, or political office.

In return for African Americans remaining peaceful and socially separate from whites, the white community needed to accept responsibility for improving the social and economic conditions of all Americans, regardless of color. He summarized his concept of race relations in this manner: “In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

Many black leaders opposed Washington’s “accommodationist” form of politics. Some historians cite the “Atlanta Compromise” as being responsible for the founding of both the NAACP and the “Niagara Movement” civil rights organizations.

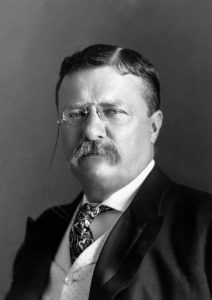

5. American Imperialism — Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine:

European intervention in the Americas resurfaced as a foreign policy issue at the turn of the 20th century. Three European nations had blockaded Venezuela’s ports in an attempt to force Venezuela to pay its international debts, violating the Monroe Doctrine’s declaration that Europe should not interfere in the Americas.

Further, Roosevelt had recently gained, through hostile action, the right to build the Panama Canal; and he believed that any threat to the canal threatened our strategic and economic interests.

Accordingly, to maintain security and ensure financial solvency in the region, the President announced, in his State of the Union address in December, 1904, that, “Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation. In the Western Hemisphere, our adherence to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of wrongdoing, to the exercise of international police power.”

Thus, the United States will intervene in conflicts between Europe and Latin America, rather than having the Europeans press their claims directly.

As a result, Marines were sent into Santo Domingo in 1904, Nicaragua in 1911, and Haiti in 1915; and, several more times in the Caribbean and Central America over the next quarter century. America’s relations with our southern neighbors remained strained for many years; and. in 1934, Franklin D. Roosevelt renounced interventionism and established his “Good Neighbor Policy” within the Western Hemisphere.

Some Final Thoughts

I am impressed with the eloquence of America’s early leaders. I have included only small portions of the actual transcripts of the historic speeches in the above; but, if I have piqued your interest at all to read the entire texts, they are readily available and require only modest search or library skills.

Note that George Washington was not restricted to two terms. However, in somewhat failing health, he feared that, if he died in office, it would establish a precedent that the presidency was a lifetime appointment. Instead, he stepped aside to make way for a successor, and demonstrated his commitment to democracy, rather than power.

There is a tradition in the Senate, wherein George Washington’s birthday is celebrated by a reading of his Farewell Address on the floor of the Senate Chamber; with readers coming from alternating parties. Although his warnings are still relevant, attendance at these readings has, unfortunately, shrunk.

Also note that historians cite Lincoln’s second inaugural address as one of the greatest speeches ever made by an American president.

Finally, Part 2 of this essay begins with Nazi aggression in Europe, and continues through Hiroshima.

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

Tom, once again, you deliver a thoughtful view for consideration.

Thank you!