Editor’s Note: Tom Gotowka sent us this piece last week, but we had always planned to publish it today. By an extraordinary coincidence, we now find — thanks to an article sent to us this morning by our friend and regular correspondent George Ryan — that today is the 90th anniversary of William Gillette’s final performance as Sherlock Holmes, given Feb. 12, 1930 at the popular Parsons Theatre in downtown Hartford.

Timing is everything … so many thanks indeed to George for his gem of information and Tom for his fascinating insight into the life and work of Mr. Gillette.

I am going a few miles upstream in this essay towards East Haddam and its medieval gothic castle to consider William Gillette’s impact on how Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed in movies and television. My goal in these essays is to cover the subject thoroughly enough to either satisfy your curiosity, or to pique your interest to pursue some additional research.

Assuming the editor’s forbearance, I will also review, in a subsequent essay, several of the actors who played Holmes or Watson to judge how true they were to either Gillette’s or Arthur Conan Doyle’s artistic vision.

Gillette was born to a progressive political family in Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood — where authors Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, and Charles Dudley Warner each once resided. His mother was a Hooker, that is a direct descendant of Connecticut Colony co-founder Thomas Hooker. Gillette is most recognized for his on-stage interpretation of Sherlock Holmes. He may have been America’s first matinée idol or to put it another way, the era’s rock star.

The Sherlockian Literature

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote 56 short stories and four novels between the 1880s and the early 20th century that comprise the “canon” of Sherlock Holmes. The stories were first published in Strand Magazine and two of the novels were serialized in that same periodical.

Holmes defined himself as the world’s first and only “consulting detective.” He shared rooms at 221B Baker Street in London with Dr. John H. Watson, who was a former army surgeon wounded in the Second Afghan War.

Holmes referred to Watson as his “Boswell” because he chronicled his life and the investigations that they jointly pursued — as did 18th century biographer, James Boswell, of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Watson was described as a typical Victorian-era gentleman and also served as first-person narrator for nearly all of the stories.

Holmes was known for his incredible skills of observation and deduction, and forensic science and logic, all of which he used when investigating cases for his myriad clients, which often included Scotland Yard. He played the violin well and was an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman. He summarized his investigative skills for Watson this way, “Once you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,” and, “It is my business to know what other people don’t know.”

However, Holmes had shortcomings. He was a very heavy smoker of black shag pipe tobacco, which he kept in the toe of a Persian slipper on the fireplace mantel at 221B. He also smoked cigars and cigarettes. A very difficult problem was called a “three pipe problem.”

He used cocaine and morphine to provide “stimulation for his overactive brain” during periods when he did not have an interesting case or as an escape from “the dull routine of existence.” This was not really unusual in that period because the sale of opium, laudanum, cocaine, and morphine was legal and often used to self-medicate or for recreation. This habit was worrisome for Dr. Watson, although he once said of Holmes, “He was the best and wisest man whom I have ever known.”

The Holmes stories were immensely popular and Doyle’s last publication in Strand, “The Final Problem,” elicited such public (and Royal Family) outrage, that there were mass subscriber cancellations bringing the magazine to the brink of failure.

Doyle decided to write a stage play about Holmes, set earlier in the detective’s career. He was probably compelled to do so because there already were several Sherlock Holmes on-stage productions, which provided him no income, and were of such poor quality that he felt the need to both protect his character’s legacy and improve his own income stream.

He drafted the play and shared it with his literary agent, who sent it on to Broadway producer and impresario, Charles Frohman. Frohman reviewed it and said it needed substantial work before anyone would consider production. He suggested that William Gillette be offered the rewriting task.

At that time, Gillette was already well-known as a talented actor and a successful and prolific playwright. His approach was a significant change from the melodramatic standards in the American theater of the time. He stressed realism in sets, lighting, and sound effects. Holmes Scholar Susan Dahlinger described Gillette’s acting style this way, “He could be thrilling without bombast, or infinitely touching without descending to sentimentality.”

So, Doyle agreed with Frohman, and Gillette began the project by reading the entire “canon” of Holmes stories and novels. He began drafting the new manuscript while touring in California with the stage production of “Secret Service,” which he had also written. He exchanged frequent telegrams with Doyle during the process and, with Doyle’s blessing, borrowed some plots and detail from the canon in adapting Doyle’s original manuscript into a four-act play.

Unfortunately, neither Gillette’s first draft nor Doyle’s original script ever reached stage production. A fire broke out at Gillette’s San Francisco hotel and both manuscripts were lost. So, Gillette began a complete redraft of his lost script, and Doyle was finally able to present a play before the century’s end that he deemed worthy of Sherlock Holmes.

It is worth noting that Frohman perished on the Lusitania in May, 1915, after it had been torpedoed by a German submarine.

In 1899, Gillette was “predictably” cast for the lead role in “Sherlock Holmes — A Drama in Four Acts.” Initially presented in previews at the Star Theatre in Buffalo, NY, it opened that November at the Garrick Theatre in New York City, and ran there for more than 260 performances before beginning a tour of the United States and then on to a long run in London, where it received great critical and public acclaim.

He starred in that role for more than 30 years, and about 1,500 productions in the United States and Great Britain. He also starred in the 1916 silent film, “Sherlock Holmes,” which film-historians have called, “the most elaborate of the early movies.”

Playing a role for so many years was not unusual at that time in American Theater. For example, James O’Neill, father of playwright Eugene, played Edmond Dantès, The Count of Monte Cristo, more than 6000 times between 1875 and 1920.

Some Key Elements of Gillette’s Sherlock

Although William Gillette is really no longer a “household name” — except perhaps,here in Southeastern Connecticut, where much of how we imagine Holmes today is still due to his stage portrayal of the great consulting detective.

Gillette actually bore some resemblance to the Holmes described by Dr. Watson in “A Study in Scarlet.” Watson notes, “His [Holmes’s] very person and appearance were such as to strike the attention of the most casual observer. In height he was rather over six feet, and so excessively lean that he seemed to be considerably taller. His eyes were sharp and piercing, and his thin, hawk-like nose gave his whole expression an air of alertness and decision. His chin, too, had the prominence and squareness which mark the man of determination.”

Gillette’s Holmes appeared in deerstalker cap and Inverness cape. He smoked a curve-stemmed briar pipe, and carried a magnifying glass. He crafted a phrase that eventually evolved into one of the most recognized lines in popular culture: “Elementary, my dear Watson.” Gillette’s direct style was said to lend a bit of arrogance to Holmes beyond that which Doyle had depicted — that arrogance has become a hallmark of Holmes’ portrayal in contemporary movies and television.

And finally, Gillette introduced the page, “Billie,” who had actually been played by a certain 13-year-old Charles Spencer Chaplin during the London engagement. At the end of the run, Chaplin began his career as a Vaudeville comedian, which ultimately took him to the United States and movie stardom as the incomparable Charlie Chaplin.

Some Final Thoughts

I first learned of William Gillette a few summers ago when I visited his remarkable home, “Gillette Castle” built high above the eastern bank of the Connecticut River. I left that visit impressed with Gillette’s creativity in his design of the doors, light switches, and some of the furniture; wondering about his secret multi-mirror “spying” system, and with the assumption that he was just an eccentric artist who liked trains.

However, I enjoy the Sherlock Holmes literature; and began reading the “canon” at age twelve. I have certainly re-read many of the stories a few more times. Over the past several years, I began to read several authors who write Sherlock Holmes short stories and novels “in the style of Arthur Conan Doyle.” Some of these “pastiches,” as they are called, are quite accurate in style and continuity of Doyle’s themes.

In researching this essay, I was surprised with the breadth of scholarly work that is currently available regarding Sherlock and Gillette. There are several national and international literary organizations that have also developed around Doyle’s work.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth offers a “Study of Sherlock” course, wherein students engage in critical reading, thinking, and writing by studying the iconic detective.

Our local expert on Holmes is Danna Mancini of Niantic. He has lectured and conducted seminars on The World of “Sherlock Holmes.” He is active in at least two Holmes literary organizations: The Baker Street Irregulars (NYC) and the Speckled Band of Boston.

Of some note, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) tasked by Winston Churchill to “set Europe ablaze” during World War II, had its headquarters at 64 Baker Street and was often called, “The Baker Street Irregulars.”

So, the ‘consulting detective’ continues to inspire novels, movies, and television.

As noted above, I will review several of the actors who played Holmes or Watson in these media in my next essay, and judge how true they were to either Gillette’s or Arthur Conan Doyle’s artistic vision.

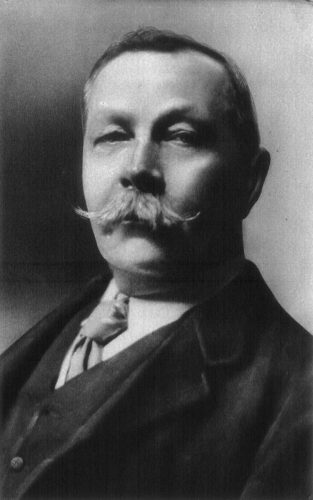

Photo credit for the photo of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is as follows: By Arnold Genthe – PD image from http://www.sru.edu/depts/cisba/compsci/dailey/217students/sgm8660/Final/They got it from: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/photodraw/portraits/,where the source was given as: Current History of the War v.I (December 1914 – March 1915). New York: New York Times Company., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=240887

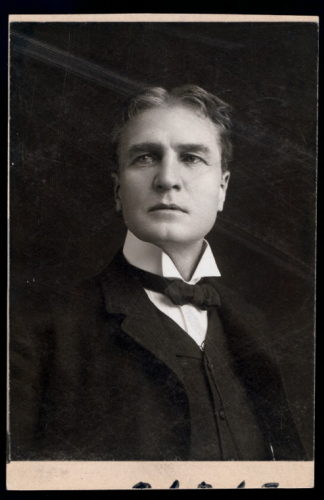

Photo credit for the photo of William Gillette is as follows: Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. William Gillette Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-e15c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He’ will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK.

A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.

“Gillette Castle” – I find that many Connecticut people near me in Westbrook know of it, boat by it, take guests to it, attend events at it, but many do not know well who Gillette was. (I also find that people confuse Gillette with the other iconic “G” in East Haddam, Goodspeed.) Thank you for placing Gillette in history for us – from Connecticut’s Nook Farm and to internationally. And thank you bringing him – and Sherlock Holmes – into our century.

All so interesting.

Tom nimbly weaves a history though Holmes, Doyle and Gillette as if they were one in the same mythological character. I am looking forward to the next installments. Thank you!

A good essay. To paraphrase Holmes, my advise to others is to read this view at once if convenient—if inconvenient read it all the same

Loved this article! I remember going to Gillette Castle as a child and still enjoy visiting with out of town guests. The wooden doors and secret “spying” system are fascinating and the views can’t be beat. Really looking forward to the next installment about the actors. Please keep these essays coming!