As you busy yourself making plans for Thursday’s feast, we are delighted to take the opportunity to republish a topical article about the evolution of this quintessential American meal that our dear friend — and wonderful writer — Linda Ahnert of Old Lyme wrote for us all the way back in 2007. Enjoy!

Who Doesn’t Love Thanksgiving?

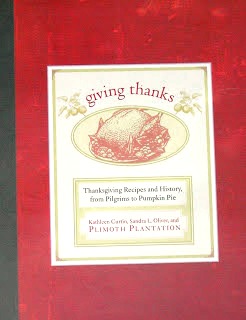

A few years ago, a book entitled “Giving Thanks: Thanksgiving Recipes and History, from Pilgrims to Pumpkin Pie” was published. The co-authors are Kathleen Curtin, food historian at the Plimoth Plantation, Mass., and Sandra L. Oliver, food historian and publisher of the newsletter “Food History News.”

A few years ago, a book entitled “Giving Thanks: Thanksgiving Recipes and History, from Pilgrims to Pumpkin Pie” was published. The co-authors are Kathleen Curtin, food historian at the Plimoth Plantation, Mass., and Sandra L. Oliver, food historian and publisher of the newsletter “Food History News.”

The book is a fascinating look at how an autumnal feast evolved into a “quintessential American holiday.”

Most Americans, introduced to the story of the Pilgrims and Indians during childhood, assume there is a direct link between the traditional holiday menu and the first Thanksgiving. But we learn from the book that many of those food items—such as mashed potatoes and apple pie—were simply impossible in Plymouth, Mass., in 1621. Potatoes were not introduced to New England until much later and those first settlers did not yet have ovens to bake pies.

What we do know about the bill of fare at the first celebration in 1621 comes from a letter written by colonist Edward Winslow to a friend in England: “Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors.”

Later 90 Indians joined the party with “their great king Massasoit whom for three days we entertained and feasted.” Then the Indians “went out and killed five deer which they brought to the plantation.”

So venison was a principal food on the menu. It also seems safe to assume that mussels, clams, and lobsters (all in plentiful supply) were served as well. According to other journals of the colonists, the “fowl” that Winslow described were probably ducks and geese. But wild turkeys were also bountiful in 1621, and so it is very likely that they were on the Pilgrims’ table. Thank goodness for that.

Throughout the New England colonies, it became common to proclaim a day of thanksgiving sometime in the autumn. In period diaries, there are many descriptions of food preparation—such as butchering and pie baking—followed by the notation that “today was the general thanksgiving.”

By the 19th century, Americans were taking the idea of a “thanksgiving” to a whole new level. The religious connotations were dropping away in favor of a holiday celebrating family and food. Roast turkey had become the centerpiece of these fall celebrations.

Turkeys, of course, were native to North America. (Benjamin Franklin, in a letter, had even proposed the turkey as the official U.S. bird!) And turkey was considered to be a fashionable food back in the mother country. Just think of the significance of turkey in Charles’ Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol.” When Scrooge wakes up in a joyful mood on Christmas morning, he calls to a boy in the street to deliver the prize turkey in the poulterer’s shop to the Cratchit family. (Earlier in the story, the poor Cratchits were dining on goose.)

It is thanks to a New England woman that Thanksgiving became an American holiday. Sarah Hale was a native of New Hampshire and the editor of “Godey’s Lady’s Book,” a popular women’s magazine. She lobbied for years for a national observance of Thanksgiving. She wrote editorials and sent letters to the president, all state governors, and members of Congress.

Finally, in 1863, she convinced Abraham Lincoln that a national Thanksgiving Day might help to unite the Civil War-stricken country. The fourth Thursday in November was now officially on the American calendar.

Connecticut’s own Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote this description of a New England Thanksgiving in one of her novels—“But who shall . . .describe the turkey, and chickens, and chicken pies, with all that endless variety of vegetables which the American soil and climate have contributed to the table . . . After the meat came the plum-puddings, and then the endless array of pies. . .”

The autumnal feast became a national holiday, but each region of the country put its own spin on the menu. Not to mention that immigrants have also added diversity. The result is a true “melting pot” of America. The second half of “Giving Thanks” contains recipes that reflect what Americans eat for Thanksgiving in the 21st century.

In the South, for instance, the turkey might be stuffed with cornbread and there would be pecan and sweet potato pies on the table. In New Mexico, chiles and Southwestern flavors may be added to the stuffing.

There’s the “time-honored traditional bread stuffing” recipe. There’s also one for a Chinese American rice dressing and directions for a Cuban turkey stuffed with black beans and rice. Desserts run the gamut from an (authentic) Indian pudding to an (exotic) coconut rice pudding. Old-fashioned pumpkin pie is included as well as the newfangled pumpkin cheesecake.

But no matter what food items grace our Thanksgiving tables, it seems that we all end up stuffing ourselves silly. Perhaps overeating started at that very first harvest celebration in 1621. In Edward Winslow’s letter describing the feast with the Indians, he noted that food was not always this plentiful. But he wrote his friend in England “ … yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”