The year 1917 in Russia marked a unique moment of history when art and revolution fused together into a mutual source of inspiration. The creativity and energy fed on each other for a short few years, to eventually vanish under the brutal repression and purges of Stalin to become an official and bland art form called “Socialist Realism.”

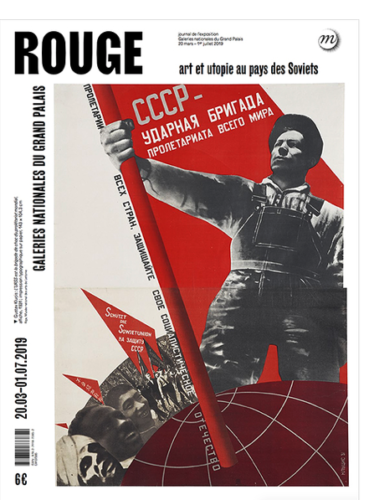

The exhibit “Red – Art and Utopia in the Soviet Country” at the Grand Palais, Paris, in the spring of 2019 is breaking new ground in describing that unique moment.

All forms of arts were impacted by the October Revolution, from the visual arts to architecture, theater, cinema, music and, of course, literature. In addition to major artists, already well known before World War I, such as Malevich, the Bolchevik government did welcome all talented artists eager to experiment with new art forms.

Mayakovsky (1893-1930) was the voice of the Revolution – a giant with a booming voice, who galvanized the crowds when he read his poetry. His emblematic play, the “Bedbug,” is a satire of the NEP (New Economic Policy.) A young man of that period is frozen and found himself in a perfect communist world 50 years later where there was no drunkenness nor swearing.

He decided he was not made for the future. As a journalist, Mayakovsky used simple street language. A gifted artist, he drew satirical cartoons, making fun of the “petty bourgeoisie.” One of the main metro stations in central Moscow was named after him. He shot himself in 1930 at the age of 37.

Malevich (1878-1935), a major artist of the 20th century, was inspired until 1914, by Gauguin, Matisse and Cezanne, and then moved to abstraction and geometric forms until he reached his extreme “White on White” in 1918. He was the theoretician of art par excellence.

His book “From Cubism to Suprematism in Art …” is considered one of the most important reference works of the 20th century. Toward the end of his life he was forced to reintroduce figurative characters into his paintings. He never left the Soviet Union where he died of cancer in 1935.

Tatlin (1885-1953) was associated with the concept of “constructivism,” based on the use of materials, the exploitation of movement and tension in matter. He aimed at the harmonization of artistic form with utilitarian goals.

Artists’ association multiplied at that time. AKhRR (Association of Russian Artists of Revolutionary Russia) was founded in 1922. Vkhutemas (higher Institutes of art and technique) were created as early as 1920 all over the country. Both Malevich and Tatlin occupied important positions in those institutions .

Vsevolod Mayerhold, (1874-1940) following in the footsteps of Stanislavsky (master of the stage in the 19th century – particularly Chekhov plays), revolutionized theatrical techniques, suppressed settings and replaced them by “constructivist” space, trained the actors according to a new system of “bio-mechanic” and how to form human pyramids. His stage production of Mayakovsky’s “Bed Bug” is emblematic of the Soviet era.

Rodchenko (1891-1956) was the leading innovator of the 1917 revolution-inspired art. He wanted to bring art down from its pedestal. He stood against estheticism and “art for art” and made art the champion of productivity. He created a new artistic language by experimenting with photography, using photo-montage, double exposures, and unexpected angles. He gloried the machine in a factory or objects of daily life rather than still life motives in traditional art.

Among this group of brilliant artists were two women – Lioubov Popova, (1889-1924), who died of scarlet fever, and Varvara Stepanova (1894-1958i), Rodchenko’s wife.

Posters became a new art form used as the most important tool of propaganda. They were intended to make a strong and immediate impact on the viewer. Using a graphic art medium with calligraphy and geometric designs, they carried a simple message. The color red was used extensively (it is interesting to note that, in Russian, “red” and “beautiful” are the same word.)

Oversize paintings like “Bolchevik” by Kustodiev are easy to understand. A giant man walks through dwarfed city landscape with churches, holding a huge red banner. The messages of the October revolution were spread throughout the country in the “agit-prop trains” to educate the masses. Some figures are impressive: in 1917 the literacy of the population was 25 percent whereas by 1939, it had risen to 81 percent.

Gustav Klutsis (1895-1935), born in Latvia, was also one of the best at using photo-montage and posters . He wrote: “Put color, slogan at the service of class war.” Klutsis was arrested and shot in 1938.

Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948) – a pioneer of the cinema – created his own style characterized by melodramatic acting, close-up shots and theatrical editing. A sequence of “Battlefield Potemkin” has become an absolute classic: during an attack by the Cossacks against Odessa civilians, a baby carriage falls all the way down the long steps.

Eisenstein ‘s mob scenes are so realistic (such as the storming of the Winter Palace in St Petersburg) that they are often mistaken for newsreels in documentaries.

Architecture played a crucial role in bringing about utopia of the proletariat. Plans for grand buildings, squares and majestic avenues are intended to impress the masses, who are more important than the individuals. Still standing today is the workers’ club Roussatov designed by Melnikov.

After the death of Lenin in 1924, power became concentrated in the hands of Stalin, who tightened his control over artists. In 1932 all artistic associations were suppressed — artists were forced to join the official Union.

The creative, innovative productions had to bend and conform to rules of the new doctrine of Socialist Realism formulated by Andrei Zhdanov in a speech to the Writer’s Union in 1934. In art, it can be defined as representation of the bright future of communism through the representation of idealized workers in healthy bodies.

Therefore, at the 1937 Universal Fair held in Paris, a double statue of a vigorous factory worker and a strong woman kolkhoz farmer stood on top of the Soviet building.

Most representative of this period was Alexander Deïneka, who painted naked, young factory workers taking a break on the beach in the Donbass or Lenin riding in an open sports car through bucolic countryside with several blonde children.

Somehow out of place in 1937 is a delightful painting by Yuri Pimenov called, “The New Moscow.” A young woman is driving a convertible car on one of the main thoroughfares of central Moscow. The style is very much in the Impressionist style.

Already in the 1990s, the Tretiakov Gallery of Moscow held exhibits on the 1920s and 1930s Soviet art. At that time, the Soviet posters were readily available in the book stores of the Arbat pedestrian street.

Although a large part of the exhibited works included in the “Red” exhibit come from the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, it is interesting to note that in the 1979 Paris-Moscow exhibit organized by that same museum, Soviet art was barely mentioned.

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Nicole Prévost Logan.

Nicole Prévost Logan

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.