In October 1900, Picasso – at age 19 – arrived at the Gare d’Orsay in Paris from Barcelona. So, it is appropriate that the Orsay Museum would host an exhibition about the young Spanish artist.

The blockbuster, which opened in the autumn of 2018, was called “Picasso. Bleu, Rose” and refers to the 1900-1906 years. It is a long overdue theme, never before treated in France.

For several reasons, this period is unique among Picasso’s long career. It reveals the precocious virtuosity of such a young person as a draughtsman;

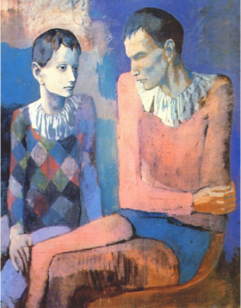

never again will he express such intense emotions; Harlequin — a main character from the Commedia del’arte — is introduced for the first time and will remain his double throughout his life’s work. The image at right shows “Arlequin with an acrobat” (1905) portrayed as a young and emaciated boy.

Between 1900 and 1904, Picasso made several trips between Spain and Paris, until he settled permanently in the French capital where he rented a studio, along with other artists, in a dilapidated building baptized the Bateau-Lavoir (washhouse.)

He liked to hang around at the tavern of Els Quatre Gats (Four Cats) in Barcelona where he met Catalan friends – such as Santiago Rusinol or Ramon Casos. The exhibit shows hundreds of the small portraits and sketches, sometimes humorous, that he created at full speed.

With a voracious curiosity, he would watch the colorful, loud crowds at cabarets, bordellos, night clubs or caf’concs (cafés with a music hall performance) of Montmartre.

Toulouse Lautrec was his idol.

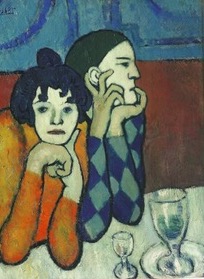

Like him, Picasso depicted the dejected night-life customers stunned under the effect of absinthe. “Arlequin and his companion” (1901, Pushkin museum, Moscow) shown at left represents a couple totally alienated from each other, sitting at a bistro table, with vacuous expressions on their faces.

The man is Harlequin, dressed in his usual costume with lozenges.

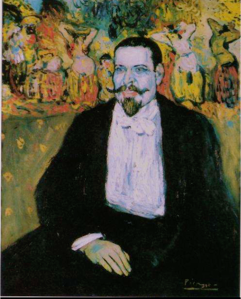

The “Portrait of Gustave Coquiot” (1901, Musee d’art moderne, Paris) at right is emblematic of this garish night life. The collector and art critic is depicted as a well-fed individual, with half naked girls dancing in the background, his mouth snarled in a lecherous grimace, under an insolent mustache.

But those years were lean years for Picasso. Both in Barcelona and in Paris Picasso lived in utter poverty.

This was the height of his “Blue Period” — the color of the bottom of the abyss. Beggars, orphans, the poor — Picasso showed his empathy for all of them.

He would take for models the former prostitutes incarcerated at the Saint Lazare prison in Barcelona, where many were dying of venereal diseases .

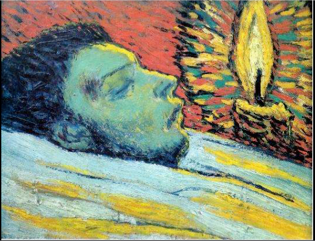

One usually links the Blue Period with the death of his close friend Casagemas in 1901 The painting at left of the young Catalan artist on his death bed, (1901, Musee Picasso, Paris) is realistic and shows the bullet wound on his temple after he committed suicide. The feverish multicolor strokes around the candle are reminiscent of van Gogh’s technique.

Abject poverty did not prevent Picasso from leading a lively, bohemian life among artists, poets, writers in the Montmartre district of the French capital, which was the center of the artistic world at that time.

The German art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler immediately discovered the genius of Picasso. Things started looking up when art merchant Ambroise Vollard bought several of his paintings. His melancholy disappeared when he fell passionately in love with Fernande Olivier, one of his many companions whose body and face he kept deconstructing.

The distinction between Blue and Pink Periods is rather artificial. Sadness lingered on through both periods.

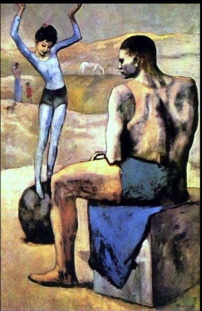

Pink became predominant when the artist became interested in the circus world. Several times a week he would go to the cirque Medrano. But unlike other artists like Seurat, Rouault or Matisse, he was not interested in the spectacles per se but rather in what happened backstage and in the miserable existence of the acrobats.

In “Acrobate a la boule” (at right), a frail adolescent is trying to keep his (her) balance on a round ball watched by a heavy set acrobat sitting on a massive cube. Art historians give a deep meaning to the scene, to the contrast between the spiritual world, taking risks, being continually in motion with the stability of life grounded in the earth.

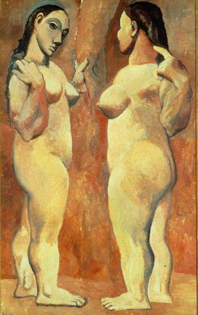

In the summer of 1906, Picasso’s life took a new turn. Being with Fernande on the hillside village of Gozolf, he seemed totally happy, enjoying the sun and inspired by the pink and ochre color of the clay. He discovered the Iberian sculptures of the fifth and sixth centuries BC influenced by Phoenician and Greek cultures as well as 12th century medieval sculptures.

His art seems to be changing course. In “Deux Nus” (1906, MOMA), shown at left, the bodies of the naked women, are deformed, with disproportionate legs and heavy torso. Picasso was ready for another discovery … African art.

Matisse showed him an African statuette in the apartment of Gertrude and Leo Stein. Picasso was stunned.

As a result, after numerous sketches, (the Steins bought most of them when Picasso was still unknown), Picasso produced the ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’ (1907, MOMA), which remains probably the most important painting of the 20th century.

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Nicole Prévost Logan.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.