How would you respond to a bearded gentleman greeting you in Lahore, Pakistan, with these words: “Excuse me, sir, but may I be of assistance?” Followed by these, “Ah, I see I have alarmed you. Do not be frightened by my beard: I am a lover of America. I noticed that you were looking for something, more than looking, in fact you seemed to be on a mission, and since I am both a native of this city and a speaker of your language, I thought I might offer you my service.”

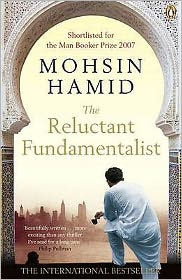

Mohsin Hamid, a native Pakistani, a graduate of Princeton University, and a former employee of a financial services firm in New York, serving clients in the Philippines, and Chile, who now lives and writes in Oxford, has created a character with similar experience to his own. The character greets this American in his native city, wines and dines with him, all while delivering his life story.

We read only the words of Changez, the name of the narrator and guide, telling us of how his views of the United States and its inhabitants have been materially altered by events at the turn of the century. It is an increasingly critical analysis. What do we citizens of this country, protected by two oceans and enormous wealth, really know what others around this globe think of us?

Consider these quotes:

“ … my ability to function both respectfully and with self-respect in a hierarchical environment, something American youngsters – unlike their Pakistani counterparts – rarely seemed trained to do.”

“I had always thought of America as a nation that looked forward; for the first time I was struck by its determination to look back … What your fellow countrymen longed for was unclear to me – a time of unquestioned dominance? Of safety? Of moral certainty? I did not know — but that they were scrambling to don the costumes of another era was apparent.”

“Yes, my musings were bleak indeed. I reflected that I had always resented the manner in which America conducted itself in the world; your country’s constant interference in the affairs of others was insufferable. Vietnam, Korea, the straits of Taiwan, the Middle East, and now Afghanistan: in each of the major conflicts and standoffs that ringed my mother continent of Asia, America played a central role … (and) finance was a primary means by which the American empire exercised its power.”

“It seemed to me then … that America was engaged only in posturing. As a society, you were unwilling to reflect upon the shared pain that united you with those who attacked you. You retreated into myths of your own difference, assumptions of your own superiority. And you acted out these beliefs on the stage of the world. So that the entire planet was rocked by the repercussions of your tantrums … “

This is a compelling and enlightening one-sided conversation, leading to a

stunning conclusion.

As the author himself comments in an addendum to this novel, “I believe that the core skill of the novelist is empathy: the ability to imagine what someone else might feel. And I believe that the world is suffering from a deficit of empathy at the moment … We need to stop being so confused by the fear we are fed; a shared humanity should unite us with people we are encouraged to think of as enemies.”

Incidentally, Hamid has written a second novel, Exit West*, which received solid reviews here and in Europe. I’ve read it, but I consider The Reluctant Fundamentalist his jewel.

Challenge your thinking!

Editor’s Notes: i) ‘The Reluctant Fundamentalist’ by Mohsin Hamid is published by Houghton Mifflin & Harcourt, New York 2007

ii) ‘Exit West’ by Mohsin Hamid was the Eastern Connecticut ‘One Book One Region’ selection for 2018.

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year resident of Lyme, he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction that explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farm Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings. His late wife, Ann, was also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visited every summer.