This is a confession of an addict.

This is a confession of an addict.

In early 1993, I was urged by a long-time sailing friend to begin reading a series of novels by Patrick O’Brian about an English skipper and his shipboard surgeon set in the Napoleonic Wars.

I did.

By now I’ve read – three times, no less –all 21 of the famous Jack Aubrey-Stephen Maturin novels, plus six of his other books, plus King’s 2000 biography. And I’ve just finished a second read of this biography, learning even more about a compelling writer, now acknowledged by many as one of the two best 20th Century tellers of sea stories (Joseph Conrad being the other.)

A re-read is often even more enlightening than the first, and so it was this time. For Patrick O’Brian was a consummate “storyteller” in both senses of the word. First, he was not “Patrick O’Brian”, an Irish novelist. He was Richard Patrick Russ, the grandson of a German who moved to London in 1842 to seek his fortune as a furrier. He served in the ambulance corps during World War II and divorced his first (Welsh) wife immediately thereafter, taking his new wife Mary (English, but divorced from her Russian husband) first to Wales and then to southern France, as his writing career blossomed.

Patrick was indeed a well-read and curious man, whose “ … love of nature, literature, and writing arrived early, whose love of solitude would endure, and whose obsession with privacy would infuse his eventual literary tour de force, the Aubrey-Maturin novels.”

But his worlds were mostly vicarious, experienced through his reading, not through actual sea experience. While his stories give us detailed and factually-correct stories of the sea and many of the battles, skirmishes, and life at sea during the wars between 1800 and 1820, plus the intrigues of life in England at that time, they were a result of his reading and research plus his remarkable memory.As far as we know, O’Brian never went to sea in any sort of vessel!

O’Brian avoided publicity whenever he could: As he had his alter-ego, Stephen Maturin, say in Truelove: “Question and answer is not a civilized form of conversation … It is extremely ill bred, extremely unusual, and extremely difficult to turn aside gracefully or indeed without offense.”

But he was, above all, a writer: “ … he found his most life-affirming moments in this fluid act of creation … For him, the creative process was largely an inexplicable one, some magical combination of conscious, and subconscious, of instinct and intellect, all clicking at once.” In addition to his English, he was fluid, “to some extent, in Italian, French, Spanish, German, Catalan and Irish and had a good background in Latin and Greek.” He also, “possessed extraordinary powers of retention and integrated this information into his lively ken.” King concludes that O’Brian had “ … an ego of iron beneath a surface of humility.”

My connection with O’Brian’s work goes beyond his novels and biographies. Two of us went to the Princeton Club in New York City in the fall of 1993 to hear O’Brian talk about his novels and read from one of them. Mesmerizing, but the high point was when we asked him to autograph copies of his latest work. With an impish smile he proceeded to do so: one with his right hand and the other with his left!

Most of his novels have beguiling conclusions, somewhat abrupt, if only to lead the reader toward the next “installment.” But he explained his endings in a conversation about writing with Maturin and a friend one evening on the rail of a ship in the Pacific in the Nutmeg of Consolation: “La betise c’est de vouloir conclure (the absurd thing is the desire to come to a conclusion.) The conventional ending, with virtue rewarded and loose ends tied up is often sadly chilling; and its platitude and falsity tend to infect what has gone before, however excellent.”

I noted that passage when I first read it and used it for the end of my own autobiography. King also cites it.

Mary O’Brian died in France in March 1998. Patrick O’Brian died, incongruously, in Dublin, Ireland, in January 2000. But his stories live on …

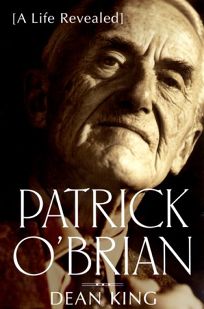

Editor’s Note: ‘Patrick O’Brian: A Life Revealed,’ by Dean King is published by Henry Holt & Co., New York 2000.

Felix Kloman

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year-resident of Lyme, he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction that explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farms Coffee. His wife, Ann, is also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a bubbling village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visit every summer.