This quote describes Sarah Vowell’s new interpretation of our history: “… I like to use whatever is lying around to paint pictures of the past …”

This quote describes Sarah Vowell’s new interpretation of our history: “… I like to use whatever is lying around to paint pictures of the past …”

The Marquis de Lafayette just happens to be her tool in this decidedly non-academic, irreverent, and often sarcastic interpretation of the effect that a rich 19-year-old French aristocrat had on our so-called “Revolution.”

Her prose is idiomatic, unpretentious, and humorous – two jokes a page! She sees our colonists as “state-sponsored terrorists, with French financial backing.” The Americans? “A squirming polygon of civilians, politicians and armed forces begging to differ.”

And she concludes: “That, to me, is the quintessential experience of living in the United States: constantly worrying whether or not the country is about to fall apart.”

Is it true that Justice Scalia read this book just before he died of apoplexy?

Ms. Vowell traces the rush of a young man from Paris to these shores, whose persuasive words and evident riches made him a general in the revolutionary forces, a youngster who rushed into battles with little experience and who contributed to the “patriot soap opera” that was our revolutionary period.

This is the seamy, seedy, and often-hilarious underside of “the ironically named ‘United’ States” and their Revolution, one that Ms. Vowell calls “FUBAR!” (I had to look that one up in Google: it means “f—ed up beyond all recognition”).

Hers is a re-interpretation of our past, richly intermixed with her current opinions.

For example: “To establish such a forthright dream of decency, who wouldn’t sign up to shoot at a few thousand Englishmen, just as long as Mr. Bean wasn’t among them? Alas, from my end of history there’s a big file cabinet blocking the view of the sweet-natured republic Lafayette foretold, and it’s where the guvment (sic) keeps the folders full of Indian treaties, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and NSA-monitored electronic messages pertinent to national security, which is apparently all of them, including the one in which I ask my mom for advice on how to get a red Sharpie stain out of couch upholstery.”

She manages to get in asides on everything: Chris Christie’s “Bridgegate” at Fort Lee (the town was named during the Revolution) and “… it must quiet the mind of Bruce Willis that even though his fellow Americans never nominated him for an Oscar, the French awarded him the Legion d’Honneur.” Another one on General Washington, who was six feet four inches tall: “Still it does get on my nerves how easy it is for tall people to make a good first impression.”

Why did the French want to support us? They had just recently been tossed out of Canada, retaining only the island of St. Pierre and Miquelon (they are still part of France …) and leaving a taste of language in Quebec. So why not send some young aristocrats to these shores, along with a few troops and some naval vessels? They agreed with many of the colonists that the Brits were “pig-headed Anglo-Saxon islanders.”

Yet this historical perambulation is an animated read. No chapter breaks, so it becomes a continuous ramble through early American history using the author’s distinctly tinted glasses. Michiko Kakutani in the New York Times called it a “cutesy-pie book.” Perhaps she is right, but its melange of historical and personal tidbits, from past and present, make it a fun trip.

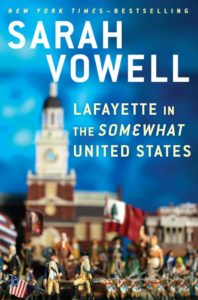

Editor’s Note: ‘Lafayette in the “Somewhat” United States’ by Sarah Vowell is published by Riverhead Books, New York 2015.

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year resident of Lyme, he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction that explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farms Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings. His wife, Ann, is also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a bubbling village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visit every summer.

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year resident of Lyme, he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction that explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farms Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings. His wife, Ann, is also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a bubbling village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visit every summer.