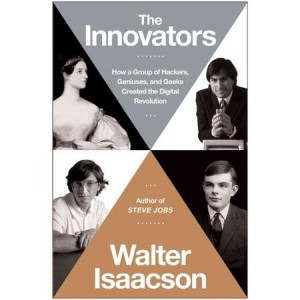

This is the remarkable and intricate story of the computer, the Internet and the World Wide Web, all of which transformed and continue to alter this globe. It is a story of human collaboration, conflict, creativity and timing, from Ada, Countess of Lovelace in 1843 to the more familiar names of Vannevar Bush, Alan Turing, John Mauchly, John von Neumann, Grace Hopper, Robert Moore, Bill Gates, Paul Allen, Tim Berners-Lee, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and, of course, “Watson,” the almost-human Jeopardy contestant of IBM.

This is the remarkable and intricate story of the computer, the Internet and the World Wide Web, all of which transformed and continue to alter this globe. It is a story of human collaboration, conflict, creativity and timing, from Ada, Countess of Lovelace in 1843 to the more familiar names of Vannevar Bush, Alan Turing, John Mauchly, John von Neumann, Grace Hopper, Robert Moore, Bill Gates, Paul Allen, Tim Berners-Lee, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and, of course, “Watson,” the almost-human Jeopardy contestant of IBM.

Isaacson stresses the importance of the intersection of individual thinking combined, inevitably, with collaborative efforts. Ideas start with non-conformists, in many of whom initiative is often confused with disobedience. But it is in collaboration that we have found the effectiveness of the Web, a “networked commons.”

These changes have come about through conception and execution, plus “peer-to-peer sharing.” Isaacson cites three co-existing approaches: (1) Apple with its bundled hardware and software, (2) Microsoft with unbundled software, and (3) the Wikipedia example of free and open software, for any hardware. No one approach, he argues, could have created this new world: all three, fighting for space, are required. Similarly, he believes that a combination of investment works best: Government funding and coordination, plus private enterprise, plus “peers freely sharing ideas and making contributions as a part of a voluntary common endeavor.”

In his concluding chapter, Isaacson raises the question of the future for AI, artificial intelligence. Stephen Hawking has warned, yet again, that we may create mechanisms that will not only think but also re-create themselves, effectively displacing homo sapiens as a species. But Isaacson is more optimistic: he sees and favors a symbiotic approach, in which the human brain and computers create an information-handling partnership. Recent advances in neuroscience suggest that the human brain is, in many ways, a limited automaton (see System One of Kahneman). But our brain, with its ability to “leap and create,” coupled with the computer’s growing ability to recall, remember, and assess billions of bits of information, may lead us, together, to better decisions.

His final “five lessons” are worth inscribing:

- “Creativity is a collaborative process.”

- “The digital age was based on expanding ideas handed down from previous generations.”

- “The most productive teams were those that brought together people with a wide array of specialties.”

- “Physical proximity is beneficial.”

- To succeed, “pair visionaries, who can generate ideas, with operating managers, who can execute them.”

Isaacson’s final lesson: humans bring to our “symbiosis with machines . . . one crucial element: creativity.” It is “the interaction of humanities and sciences.”

And we wouldn’t have LymeLine without the Innovators!

Editor’s Note: “The Innovators” is published by Simon & Schuster, New York 2014.

About the author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year resident of Lyme, he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction that explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farms Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings. His wife, Ann, is also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a bubbling village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visit every summer.