Have we over-sanctified the American past in the last 50 years? It may well be, argues Pauline Maier, a professor of history at MIT, in her now-classic analysis of the creation of our Declaration of Independence.

Have we over-sanctified the American past in the last 50 years? It may well be, argues Pauline Maier, a professor of history at MIT, in her now-classic analysis of the creation of our Declaration of Independence.

Three key documents epitomize the start of “these” United States: the Declaration, the Constitution, and its following initial amendments, the Bill of Rights. They are indeed worthwhile documents to study, but are they as perfect as we have been led to believe?

Professor Maier argues the Declaration was a product of “the grubby world of eighteenth-century politics,” with contributions from “a cast of thousands.” Its impetus came from a growing belief that monarchy and hereditary rule were “major constitutional errors.”

The simple distance from Great Britain had much to do with their dissatisfaction, too, coupled with insensitive colonial taxation.

She recalls the history that led to the Declaration. First came the English Declaration of Rights that permitted the nobility to restrain the monarch in 1689. But a short sequence of events in 1775 pushed the Continental Congress to action: the Battle of Lexington on April 18-19, 1775, the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by some out-of-control colonials on May 9, Bunker Hill on June 17, the British destruction of Falmouth (now Portland), Maine on Oct. 17, and a similar assault on Norfolk, Va., in January 1776.

By then many states had already declared their removal from English authority, creating enormous pressure on the delegates In Philadelphia during the spring, that pressure spurred the delegates to take joint action. Many state and local governments had already declared their “independence” by July 1776.

As Professor Maier notes, “ . . . the society that adopted Independence was national to a remarkable extent considering that before 1764 the North American colonies had no connection with each other except through Britain.” After 1764 they expressed their “sense of shared grievances.”

While the prime movers of the rushed Declaration in Philadelphia were indeed Thomas Jefferson and his designated “committee,” including John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Thomas Pickering, and, belatedly, Benjamin Franklin, the author argues that many others contributed to its phraseology through prior words and documents, and indeed the Congress altered the Committee’s draft afterwards, before it was published.

It is a fascinating story, especially in that the Declaration seems to have been largely disregarded after it initial acceptance, only to become sanctified when the Federalists and Republicans tussled with each other in the 1820s.

And only more recently have we tried to deify both the words and its creators.

Professor Maier carefully dissects words, phrases, and their contributors, creating a convincing thesis that the Declaration was the work of hundreds, not a few, and that, as a “peculiar document,” it hardly deserves its later sanctification.

She concludes: “The symbolism is all wrong; it suggests a tradition locked in a glorious but dead past, reinforces the passive instincts of an anti-political age, and undercuts the acknowledgement and exercise of public responsibilities essential to the survival of the republic and its ideals.”

By all means read the Declaration, but let’s move on and deal with the present using all that we now know.

It is not “scripture.”

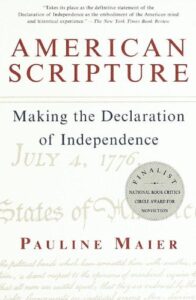

Editor’s Note: ‘American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence,’ by Pauline Maier is published by Vintage Books, New York 1998.

Felix Kloman

About the Author: Felix Kloman is a sailor, rower, husband, father, grandfather, retired management consultant and, above all, a curious reader and writer. He’s explored how we as human beings and organizations respond to ever-present uncertainty in two books, ‘Mumpsimus Revisited’ (2005) and ‘The Fantods of Risk’ (2008). A 20-year resident of Lyme, Conn., he now writes book reviews, mostly of non-fiction, a subject which explores our minds, our behavior, our politics and our history. But he does throw in a novel here and there. For more than 50 years, he’s put together the 17 syllables that comprise haiku, the traditional Japanese poetry, and now serves as the self-appointed “poet laureate” of Ashlawn Farm Coffee, where he may be seen on Friday mornings.

His late wife, Ann, was also a writer, but of mystery novels, all of which begin in a village in midcoast Maine, strangely reminiscent of the town she and her husband visited every summer.