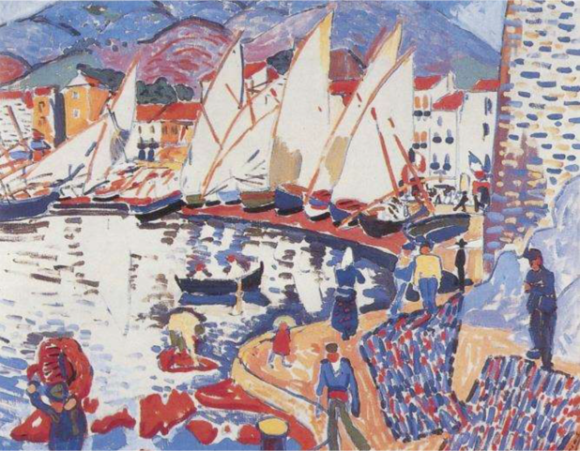

André Derain usually evokes cheerful scenes of sailboats bobbing up and down in the bright colors of a Mediterranean fishing port.

Actually, Derain (1880-1954) is a complex artist, who had a strong influence on the evolving avant-garde movements at the start of the 20th century. The Pompidou Center is currently holding a retrospective titled, “Derain – 1904-1914. The radical decade.”

The curator of the Pompidou exhibit, Cecile Debray, comments, “Derain is the founder with Matisse of Fauvism and an actor of Cezanne’s Cubism with Picasso.” Never before had the artist been attributed such a crucial role. Derain was not only the link between the masters — Gauguin and Van Gogh — and the next generation of artists, but also an explorer of new sources of inspiration, including primitive Italians, along with African and Oceanic art.

To quote Gertrude Stein (the writer and art collector famous on the cultural Parisian scene in the 1920s and 1930s), “Derain was the Christopher Columbus of modern art, but it is the others who took advantage of the new continents”

Not interested in the career of engineer planned for him by his father, the young Derain preferred to spend all his time at The Louvre, copying the classics. He shared a studio with his friend Vlaminck on the Chatou island northwest of Paris where he was born. His first paintings had as subjects the Seine river, its banks and bridges, and the activities of workers. He displayed a distinctive technique of fast brush touches, (slightly different from “pointillism“), innovative plunging views and cropping, which give his works the spontaneity of photographic snapshots.

In the summer of 1905, he spent the summer in Collioure with Matisse and was dazzled by the Mediterranean light. Derain defined light as the negation of shadow. He writes, “Colors become cartridges of dynamite casting off light.” The room VII of the 1905 Salon d’Automne, called “la cage aux fauves,” caused a scandal, (fauves mean wild animals.) In 1907, the Russian art collector Ivan Morozov acquired Derain’s paintings from the merchant Ambroise Vollard for the sum of 600 francs.

The following summer, Derain continued to work with Matisse at l’Estaque, near Marseille. His compositions became more structured, with strong lines, volumes, perspectives and plans. He still used arbitrary colors.

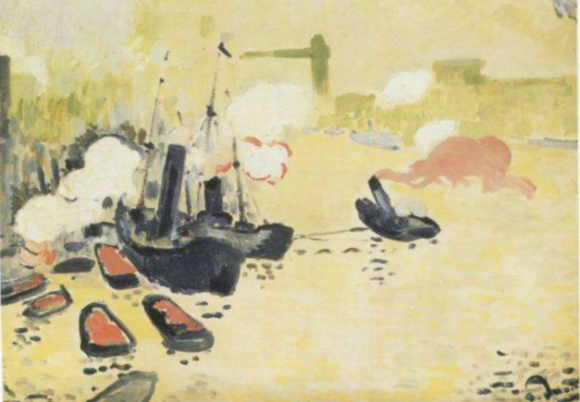

During two visits to London, he became fascinated by the bustling traffic of barges and tugboats on the Thames. He used the puffs of smoke mixed with the mist to decline all shades of whites. He found a new inspiration in the representation of water and sky. The apotheosis is an almost abstract sunset with the sun breaking through the dark clouds as if putting the sky on fire.

In 1910, Derain is part of the Cubist movement as shown in his representation of the village of Cagnes – an assemblage of cubes with red roofs scattered on a hilly landscape made of geometric lines and volumes of dense vegetation.

The versatility of Derain seems to be boundless. He played the piano, was a professional photographer, and enjoyed fast cars (he owned 11 Bugattis.) Using his virtuosity as a draughtsman, he created illustrations for humor publications along with stage and costume designs (for Diaghilev and the Russian ballets.)

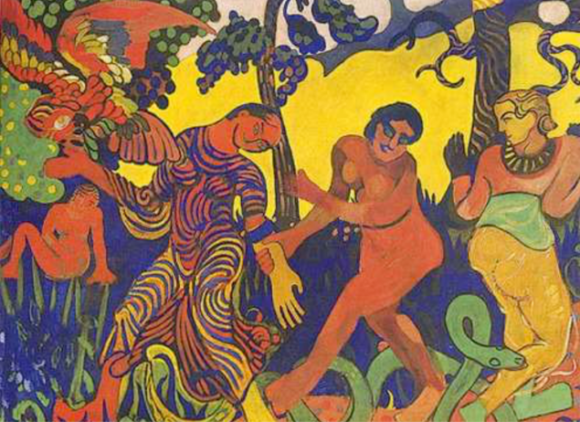

Before leaving the exhibit, the visitor will be stunned by The Dance, 1906 – a large (185 x 228 cm) decorative composition of three women undulating in a luxuriant forest. The work is rarely seen, since it belongs to a private collection. Derain was inspired by a poem by Apollinaire and called it L’Enchanteur pourrissant (the rotting magician) about three fairies looking for Merlin’s tomb. The gestures of the dancers are reminiscent of Egyptian and Indian art, and could have inspired Nijinsky’s choreography. The mysterious vegetation and the hidden meaning of a snake and a multicolored parrot infuse the ritual scene with symbolism.

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Nicole Prévost Logan.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.