It is a well kept secret that Switzerland’s private foundations own a wealth of art works. Swiss law does not require them to be registered commercially and offers them favorable tax and legal conditions, creating thus a “paradise” for art collectors. The Villa Flora, in Winterthur near Zurich, is one of the richest of these family foundations. Since the museum is under renovation this winter, its contents found a temporary home at the Marmottan Monet museum in Paris and currently form the Villa Flora exhibition subtitled, “A Time of Enchantment.”

In 1898 Hedy Hahnloser inherited from her father, a well-to-do textile industrialist, a large house and moved in with Arthur, her husband. For a short time, Arthur practiced ophthalmology in the clinic he installed on the property but soon the couple became fully engaged in the passion of their life, which was to create long-lasting friendships with painters and to collect their works.

Over the years, the rambling house was turned into a studio and an art gallery — every available space was used to place the paintings. Hedy had always been interested in arts and crafts and in the English movement by that name. She decorated her house’s parquets and wainscots with the geometric designs characteristic of the 1897 “Viennese Recession” led by Gustav Klimt.

A trip to Paris in 1908 was for the couple a total immersion into the frantic artistic scene of the French capital. Braque and Picasso were experimenting with cubism, while the Fauvist movement was at its pinnacle. The natural flair of the Hahnlosers in selecting art work was sharpened by their contacts with art merchants like Ambroise Vollard and Gaston Bernheim.

During that trip they met and struck up a friendship with Felix Valloton (1865-1925), who became a close friend, spent much time at the Villa Flora and also introduced them to the artistic circles of Paris. They remained friends until his death. For the Swiss couple to welcome artists and hold Tuesday coffees became a way of life.

One can compare their creative and welcoming home with the boarding house in Old Lyme, Conn., where Florence Griswold invited American Impressionists. Or consider Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo who, like Arthur and Hedy, opened their “salon” on 27 rue de Fleurus to artists and writers. And in yet another example, in the late 19th century, Russia also had its own artist colonies, which grew around enlightened members of the nobility. The best known was Abramtsevo, near Moscow, created by the industrialist Savva Mamontov.

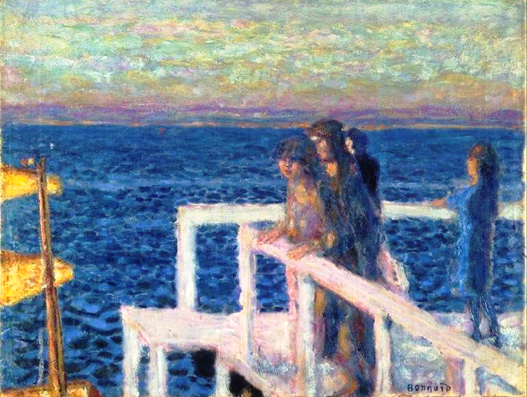

de Cannes, 1928-1934

The Hahnlosers’ collection contained works by Cezanne, Van Gogh, Manet, Renoir, Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, the symbolist Odilon Redon and many others. But it is the abundance of Nabis’ art, which made it quite unique.

It was a post-impressionist movement in the mid 1890s. “Nabi” means prophet in Hebrew and Arabic. The leading members of this group — Maurice Denis, Felix Vallotton , Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard — considered themselves as the prophets of a new era in the arts. Each one had his distinctive style, but there was always a message behind their way of depicting reality, whether it was religious, intellectual or emotional. They were versatile artists, working in oil, and also lithography, wood cuts, satirical drawings, and book or poster illustration.

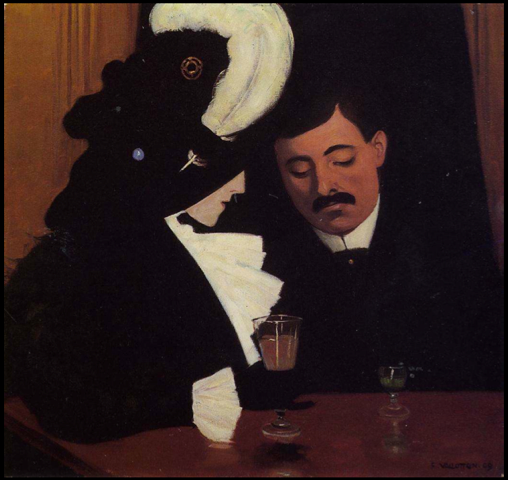

Vallotton stylized his subjects and used the technique of “aplats” or flat areas of contrasting colors with sharp outlines. There is a feeling of enigmatic emptiness in his works. “La Charette” or cart drives away on a deserted dirt road, two slender umbrella pines contrast with the darker mass of trees bordering the road.

“Le provincial,” pictured above, shows a couple in a cafe. One barely sees the profile of the elegant woman wearing a huge hat. The feather on the hat and the ruffled blouse are the only bright notes in this scene of a non-communicating couple in the male chauvinistic society at the turn of the 20th century.

Vallotton’ masterpiece is “La Blanche et la Noire” (The White and the Black). A white woman is lying, unabashedly naked, on a bed while a black woman is staring at her with insolence and a sort of inappropriate familiarity, a cigarette is sticking out of her mouth. The painting is reminiscent of the “Olympia” by Manet but with a different underlying story.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Bonnard’s paintings have an effusive and warm quality. His colors are luminous, his brush strokes seem unbridled, full of life. He is inspired by the intimacy of domestic scenes — “Le Tub” is a picture within a picture thanks to the mirror placed at the center of the composition. A plunging angle reveals Marthe, his wife and beloved model, near the tub.

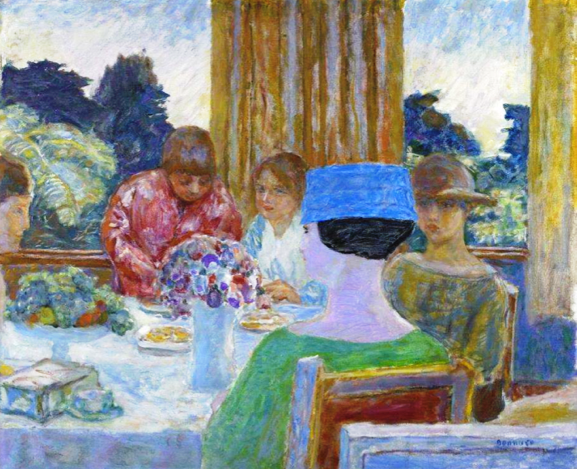

Bonnard cherished his villa in the Var, not far from Cannes. “Le Thé” is a peaceful scene of young women having tea . He plays with an array of hat colors. The vegetation seems to overflow into the porch. On “Le Debarcadère” or pier, young people lean over a railing, as if frozen in the contemplation of the rough Mediterranean waters.

This is indeed a rare opportunity to see an exceptional private art collection created by two extraordinary citizens, who according to the exhibition’s guide, lived their lives by following a simple mantra, “Living for art. Collecting. Such was the raison d’être of [this] couple.”

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.