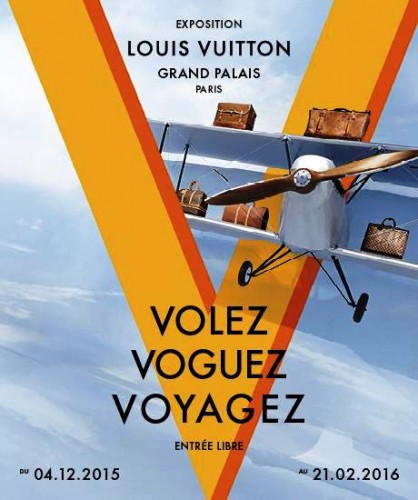

The exhibit “Volez, Voguez, Voyagez” (Fly, Sail, Travel) at the Grand Palais takes the visitor to the elegant world of travel in the early 20th century. It is a retrospective of the luggage, which created the Vuitton dynasty’s fame. Every item is beautifully crafted of wood, cloth and leather, such as the famous “sac Noé” created in 1932.

These luxurious objects make travel by air, train or sea glamorous and modern. The visitor rides an old-fashioned, wood-paneled train and feels transported into the “Out of Africa” world of Karen Blixen, as the Kenya savannah speeds outside the windows. Several pieces of the Vuitton family’s private luggage — first seen by the public at the 1900 Exposition Universelle (World Fair) — are scattered on sand dunes, evoking the beautifully photographed scene of a couple riding in the desert near the Pyramids in the 1978 Agatha Christy’s movie “Death on the Nile.”

These luxurious objects make travel by air, train or sea glamorous and modern. The visitor rides an old-fashioned, wood-paneled train and feels transported into the “Out of Africa” world of Karen Blixen, as the Kenya savannah speeds outside the windows. Several pieces of the Vuitton family’s private luggage — first seen by the public at the 1900 Exposition Universelle (World Fair) — are scattered on sand dunes, evoking the beautifully photographed scene of a couple riding in the desert near the Pyramids in the 1978 Agatha Christy’s movie “Death on the Nile.”

A huge sail reaches all the way to the ceiling. On the deck of a yacht are displayed a wooden trunk, fragrant with camphor wood and rosewood; a “wardrobe” trunk whose drawers and hangers contain an elegant passenger’s apparel; a gentleman’s personal case complete with crystal flasks; and fancy hair brushes.

Luxury goods – labeled as “consumer discretionary” in Wall Street jargon – are an important sector of the French economy. They combine traditional savoir-faire acquired over many generations (the Maison Vuitton has existed since 1835; the Maison Hermes since 1837) with the creative talent of artists and decorators along with the highly complex robotic machinery used to fabricate, clothes, bags, shoes and more.

At Hermes, silk screen scarves are made from raw silk spun under the constant scrutiny of a worker; artists, assisted by colorists, create the designs.

For decades, not a single famous woman – from Jacqueline Kennedy to French actress Catherine Deneuve – has been seen without the iconic Chanel purse. The making of the little black purse, with its gold chain, and its distinctive padded outer shell stitched in lozenges, requires the skilled delicate work of 17 people.

The world of fashion and luxury objects could not exist without money — lots of money. In 1987, the merger of Louis Vuitton fashion house with Moët et Chandon and Hennessy champagne – produced the LVMH multinational conglomerate. It brought together 90 of the most famous brands of wines and spirits, fashion and luxury goods, as well as perfume and cosmetics. Dior is the major shareholder with 40 percent of the shares.

Bernard Arnault is CEO of both Dior and LVMH. He is the richest man of France and holds the fifth largest fortune in the world — his worth is about 30 billion dollars. When Arnault arrived in Shanghai for the opening of a new Vuitton boutique, he was received like a head of state.

It is not uncommon for a tycoon to be a philantropist and an art collector. In the late 19th century, two Russian businessmen were instrumental in bringing French art to their home country — Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin introduced Impressionist art to Russia after a trip to Paris, and similarly, Ivan Morozov was a major collector of French avant-garde art.

Arnault won a resounding victory over his rival Francois Pinault when he was able to build his art museum on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. (Pinault “only” owns a few islands of Venice.) In order to promote artistic creation, Arnault built a museum, which he called the Fondation LVMH — it was designed by the American architect Frank Gehry. At the time of its inauguration in 2014, it was met with a mixed reaction but gradually it has become part of the landscape. It did help rejuvenate the dilapidated Jardin d’Acclimatation, a 100-year-old zoo and children’s attraction park, beloved by the Parisians.

Gehry created a wild structure of huge, curved glass panels flying in all directions, like spinnakers blowing in the wind. To create an area of 125,000 square feet of molded glass, 100 engineers were employed who were supported by Dassault Systèmes, the leading French company specializing in aeronautics and space.

The inside structure, called the “iceberg,” is erratic and disorients visitors. Several intricate levels and vertiginous staircases lead to the upper terrace offering a view over the Bois in which the skyscrapers of La Défense district appear to be framed by the glass panels.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.

About the author: Nicole Prévost Logan divides her time between Essex and Paris, spending summers in the former and winters in the latter. She writes a regular column for us from her Paris home where her topics will include politics, economy, social unrest — mostly in France — but also in other European countries. She also covers a variety of art exhibits and the performing arts in Europe. Logan is the author of ‘Forever on the Road: A Franco-American Family’s Thirty Years in the Foreign Service,’ an autobiography of her life as the wife of an overseas diplomat, who lived in 10 foreign countries on three continents. Her experiences during her foreign service life included being in Lebanon when civil war erupted, excavating a medieval city in Moscow and spending a week under house arrest in Guinea.