A View from My Porch: The Shady History of Connecticut Tobacco — The Finale

It’s been a little while since the publication of Part 1 of The Shady History of Connecticut Tobacco , but during that hiatus, there has been other remarkable news covered in the media.

Decisions regarding COVID mitigation were moved to municipal leadership, including school superintendents. Judge Ketanjii Brown Jackson, who was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Biden, was confirmed by the Senate, and became both the first African-American woman and native Floridian to serve on the “highest court” in the U. S. Federal Judiciary.

Without provocation, Russia brutally and relentlessly attacked Ukraine; arousing support for the courageous citizens defending their homeland by nearly the whole of the free world, and the emergence of President Volodymyr Zelensky as a leader somewhat reminiscent of a wartime Winston Churchill.

Locally, Old Lyme announced the availability of American Rescue Plan economic recovery and community initiative grants for small businesses and non-profits.

Finally, and much closer to my home, my son landed in Bahrain on an extended U.S. Navy mission with a multi- national coalition task force charged, “to provide reassurance to merchant shipping in the Middle East.” On some days, reciting the lyrics to Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain …” is a good distraction for his parents, along with, “Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?”

Part 1 Redux:

The prior essay provided some historic context for the development of tobacco farming in Connecticut. I reviewed the initial stages of the international tobacco trade, beginning with the early voyages of the Spanish and Portuguese explorers in the “Age of Discovery”. I considered how the English developed their insatiable appetite for what King James I called a “noxious weed.”

I reflected on England’s dependence on Spain as their primary source for tobacco; which resulted in a substantial trade deficit that has been cited by many historians as a precipitating factor in the decision by King James to establish a permanent colony in the Americas in 1607.

Unfortunately, the Jamestown, Va. colony was nearly doomed to fail when the settlers disembarked onto a swampy and infertile peninsula infested with malaria – carrying mosquitos; and absent the wealth and riches that the Spanish brought home after looting the Aztec empire; nearly became a financial disaster for investors.

The colony was on the brink of disaster by1610, when John Rolfe arrived in a convoy with additional settlers and supplies. Rolfe began cultivating tobacco and developed the colony’s first profitable export. His tobacco proved immensely popular in England; and by 1617, the colony’s tobacco exports had broken the Spanish monopoly, and strengthened the colony’s economy.

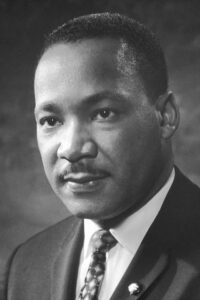

In this essay, I review the expansion of English settlements into New England, focusing on how tobacco developed as an important cash crop in Connecticut; and discuss how Martin Luther King, Jr.’s experience on a tobacco farm in Connecticut’s Farmington River Valley in the 1940s so remarkably impacted his life.

I’ll consider both the key features of the tobacco farms landscape that we observed near West Simsbury; and the romanticization of Connecticut tobacco in literature and cinema.

The Connecticut Colony:

Connecticut began as several separate settlements by the English separatist Puritans (the “Pilgrims”) from Plymouth, Mass. and England; all of which united under a single royal charter as the Connecticut Colony in 1663.

One of the earliest of these adventurers was William Holmes, who in 1633 brought a party of traders from Plymouth aboard the colony’s “great new barke.” After sailing up the Connecticut River and past a hostile Dutch fort downstream from what is now Hartford, he established the first English settlement in Connecticut at the convergence of the Farmington and Connecticut rivers at present-day Windsor.

Despite the challenge of smallpox and some sporadic combative relations with local native Americans, the Windsor settlement succeeded, and eventually contained what later became the “daughter towns” of Barkhamsted, Bloomfield, Enfield, the Granbys, Litchfield, Simsbury, Suffield, and others.

Connecticut’s Tobacco Valley:

When the first settlers came to the Connecticut River Valley, tobacco was already being grown and consumed by native Americans (i.e., the Podunk peoples), who used it in pipes. The Windsor area’s exceptionally fertile sandy loam soil and hot, humid summers were perfect for growing tobacco; and, in less than 10 years, the settlers had imported tobacco seeds from Virginia and harvested their first tobacco crop.

The earliest Connecticut tobacco variety, ‘shoestring,’ was mainly for use in pipes, but, given the settlers’ English heritage, was also brewed and consumed as a tea.

By 1700, tobacco was being exported to European ports; and in the mid-19th century, Connecticut’s Tobacco Valley, which runs from Hartford to Springfield, had become the center for tobacco agriculture in the state. Note that tobacco farms also flourished in Connecticut’s Farmington River Valley towns, westward from Windsor to Simsbury.

Cigars:

The origin of cigars has been traced back to the 10th century Mayan civilization in Central America. There is no record of the Mayans trading with the early Windsor settlers.

Connecticut folklore credits General Israel Putnam, of Brooklyn, Conn., who fought with distinction at the Battle of Bunker Hill, with increasing the popularity of cigars in New England when he returned from an expedition to Cuba in 1762 with thousands of Havana cigars.

“Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” is often attributed to Putnam at Bunker Hill.

‘Shoestring’ was replaced with ‘Broadleaf,’ a variety from Maryland, favored because the leaf was much larger, produced greater crop yields, and was suitable for cigars — although used primarily for the two outside layers, the binder and the wrapper.

Note that most cigars are comprised of three separate components: the shredded filler, the binder leaf that holds the filler together, and a wrapper leaf, which is often the highest quality leaf used.

Connecticut ‘Broadleaf’ was grown in direct sunlight, which toughened the leaf and produced a more rugged look — much rougher in texture and appearance. This eventually put Connecticut farmers at a disadvantage against others producing a more pristine leaf for cigars.

The Origins of Connecticut Shade Tobacco:

By the turn of the 20th century, cigar makers were using tobacco from Sumatra, which competed fiercely with Connecticut-grown wrapper tobaccos, and threatened the livelihood of Connecticut growers.

Science:

W. C. Sturgis, a Connecticut botanist, had already grown Sumatra tobacco from seed in 1899, reproducing the thinner leaf. During the initial trials, natural sunlight scorched the leaves. Learning that the tobacco-growing season in Sumatra occurred predominantly in overcast weather or under jungle shade, however, he erected cheesecloth tents over the experimental crops to block direct sunlight.

Botanists from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) also began experimenting with tropical tobacco varieties.

Marcus Floyd, the USDA’s leading tobacco expert at the time came to Connecticut to oversee the first crop of this experimental tobacco, now known as “shade tobacco.”

Results exceeded expectations; the tobacco leaves were more refined, and a golden leaf emerged after curing and aging; and today is considered the gold standard of cigar wrapper leaves.

Connecticut appropriated $10,00 in 1921 (over $158,000 today) for the Tobacco Research Station in Windsor to investigate cigar wrapper tobacco production and disease control.

Note the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, the first such operation in the United States, had been established in 1875.

Connecticut’s Transition to Shade:

Connecticut farmers were accustomed to the simple cultivation process and single harvest of broadleaf tobacco. In contrast, Connecticut tobacco historian, Dawn Byron Hutchins estimates that each shade tobacco leaf is handled 12 times before it becomes part of a cigar.

She describes the cultivation of shade-grown tobacco as more labor-intensive and more complicated. To wit, the growing season begins in May with weeding and transplanting seedlings. As the plants grow, they are fastened to guide wires, and then cloth tents are spread over them to increase humidity, protect the tender plants from direct sunlight, and maximize the short New England growing season.

The remainder of cultivation takes place by hand. Field workers spend weeks in high humidity and extreme heat moving among the rows, pulling off shoots and tobacco worms. Multiple harvests of leaves are brought to barns, where workers sew the leaves together to string on wooden lath. The laths are then hung in the rafters of barns to cure.

After curing, the tobacco is moved to sorting sheds and warehouses, where processing continues throughout the rest of the year.

“Working Tobacco”:

Prior to the First World War, the Greater Hartford-Springfield area was able to fulfill the need for seasonal tobacco workers with residents and immigrants. When war broke out, however, many workers were drafted, while those remaining home took jobs at munitions and other defense-related plants, which promised higher wages.

Consequently, Connecticut’s tobacco farms began to employ migrant laborers from the South and the Caribbean.

The Connecticut Tobacco Company advertised in the New York World in 1915 for “500 girls to work as sorters”. The planters “gathered up 200 girls of the worst type, who straightaway proceeded to scandalize Hartford” (sic). The blunder was managed and Emmett J. Scott, secretary-treasurer of Howard University, included the incident in his 1920 book, “Negro Migration During the War”.

The Company then sought assistance from the National Urban League (NUL), who already served as a clearinghouse and civil rights advocate for African American migrants to the North. They placed advertisements in African American newspapers like The Chicago Defender, which was circulated in the South. Unfortunately, this program was similarly unable to produce a reliable labor force.

Marcus Floyd (see USDA above), president of the Connecticut Tobacco Company since 1911, then began investigating recruitment of a special group of Southern workers: college or college-bound students. At that time, students from historically black colleges were already accompanying their professors north to work seasonal service jobs at New England resorts.

College students provided Connecticut growers with an English-speaking, educated work force, “who, as seasonal workers, would have only limited impact on the local communities”.

The NUL introduced Floyd to Dr. John Hope, the first black president of Morehouse College. A deal was struck, and Floyd recruited the first Morehouse students for the 1916 season at Hazelwood plantation on the Windsor/East Granby border.

The Hartford Daily Courant reported in August 1916 that “students were paid $2.00 per day, and, in turn, paid $4.50 per week for room and board. Students could clear $100 for the entire summer,” which is equivalent in purchasing power to more than $2,500 today. Roundtrip transportation was covered for those who completed the entire season.

Recruiters also sought student workers from other historically black colleges, including Florida A&M, Morris Brown College, Howard University, Livingstone College, and Talladega College. Growers minimized their labor problems by developing residential camps or building dormitories on their tobacco farms and providing religious and social opportunities.

A Morehouse dormitory was built in 1938 in Simsbury, and was expanded in 1946.

Martin Luther King, Jr.:

After qualifying for early admission to Morehouse College, MLK left the South to work the summers of both 1944 and 1947 on the Cullman Brothers tobacco farm in Simsbury to earn money for tuition.

“For him and a lot of the students, it’s their first time out of the South and away from segregation,” said Clayborne Carson, senior editor of “The Papers of Martin Luther King Jr.,” which included MLK’s teenage letters home describing the liberating experience of escaping the segregated South.

He was struck by the distinction between the segregation on the train ride from Atlanta to Washington D.C. and the freedom he experienced after changing trains for Connecticut. “After we passed Washington, there was no discrimination at all,” he wrote to his father; adding that up North, “We go to any place we want to and sit anywhere we want to.”

He wrote in his autobiography, “It was a bitter feeling going back to segregation after those summers in Connecticut. It was hard to understand why I could ride wherever I pleased on the train from New York to Washington and then had to change to a Jim Crow car (i.e., racially restricted) at the nation’s capital to continue the trip to Atlanta. I could never readjust to the separate waiting rooms, eating places, and rest rooms; partly because the “separate was always unequal”; and partly because the very idea of separation did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.”

Corey Kilgannon wrote in the New York Times that the dream of equality that MLK first glimpsed in Simsbury helped reshape his world view. He adds, “It was during those summers that King began his path to becoming a minister. He decided to attend Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, and explained in his 1944 application that he felt, “An inescapable urge to serve society.”

He was ordained as a minister at Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1948.

Literature and Cinema:

The 1952 novel, East of Eden, by John Steinbeck is set primarily in the Salinas Valley, although an early portion of the novel is set on a Connecticut tobacco farm. This is a very cruel story and describes the overlapping fates of several generations of two families, the Trasks and the Hamiltons; and the toxic relationship of bible-thumping Cyrus with his sons, Adam, and Adam’s violent half-brother, Charles.

Many reviewers cite East of Eden as Steinbeck’s best work and an allegory for the story of Cain and Abel. The 1955 movie, which is based on the fourth and final part of the novel. starred James Dean and Raymond Massey.

The 1958 novel, Parrish, by New London native, Mildred Savage, tells the story of the shade tobacco industry in the Connecticut River Valley in the 1940s and 1950s, and the violent conflict between the established growers, who had owned vast farms for generations, and a ruthless outsider, Judd Raike, who threatened them through hostile and underhanded acquisitions of their farm lands.

Parrish McLean and his mother work for the Sala Post tobacco farm, which is engaged in a brutal conflict with Raike. Mrs. McLean marries Raike, who then insists that the recalcitrant Parrish learn the business from the ground up; and the story proceeds from the point of view of Parrish, who still has a relationship with Sala.

The 1961 movie starred Troy Donahue (as Parrish), Claudette Colbert, and Karl Malden. It was filmed in Windsor and includes some amazing aerial panoramas of the shaded fields and farm landscapes of the time (available via Phoebe.)

I can’t close the book on Windsor without mentioning the 1941 Joseph Kesselring Broadway play and 1944 Frank Capra movie, Arsenic and Old Lace, starring Cary Grant. Arsenic was based on events at the Archer Home for Elderly People and Chronic Invalids on Prospect Street in Windsor, Conn. Sixty men died between 1907 and 1917 while in the care of Amy Archer-Gilligan. Most were proven to be victims of arsenic poisoning.

Tobacco Farms Landscape:

I mentioned last time that I was first introduced to tobacco farming when I did several years of active duty in the late 1970s at a Naval Hospital in Southern Maryland. I “mustered out” to Connecticut, and we settled in West Simsbury. We had anticipated dairy farms, and a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, but we also got fields of shade tobacco. I reminisce a little on our initial impressions in what turned out to be our final stop in an unplanned odyssey amongst the tobacco-centric regions of the eastern United States.

Making the Shade:

Tobacco fields are arranged in a grid pattern, set with posts and connecting wires. Cheesecloth was stretched across the top and along the sides. Currently, nylon mesh is used in lieu of cheesecloth. The shade diffuses sunlight, encapsulates heat and humidity, and creates an environment whose temperature is much higher than outside the shade.

Tobacco Barns:

Adjoining the fields are very distinctive, vertically-sided weathered barns, raised for curing tobacco, which is hung on stalks in the barn’s rafters. The barns are constructed with long narrow boards, which are hinged at the top. Called “Yankee hinges”, they are designed to swing open when needed in order to lower the temperature and increase air flow in the barn.

Note that there are barn designs other than the “Yankee hinges,” which are also used for curing tobacco. They include horizontal siding with top-hinged vents and gable-end doors, or a series of large doors along one of the long sides of the building with the other sides of the building vented.

Epilogue:

Tobacco production in Connecticut today is a fraction of what it was at its peak in the 1930s, when 30,000 acres of farmland grew tobacco; reflecting an overall decline in cigar smoking from a century ago, and greater public awareness of smoking-related disease. At present, just over 2,000 acres are dedicated to tobacco production.

The method of growing tobacco under shade is now common in many areas, including the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Cuba.

Connecticut seed tobaccos are also grown in a number of other countries; most notably, Ecuador.

The three-story Morehouse dormitory, mentioned earlier, which originally housed hundreds of tobacco workers, was still in service when we arrived in West Simsbury, but was weathered and in the early stages of disrepair and dilapidation. It was destroyed by fire in 1984 as part of a training exercise for volunteer firefighters.

In spring 2021, the vacant 288-acre site of the 1940s Cullman Brothers tobacco farm in Simsbury, then called Meadowood, was slated for a development of hundreds of homes. As noted above, MLK worked the summers of 1944 and 1947 on the farm.

Richard Curtiss, a history teacher at Simsbury High School, initiated a student project to investigate what was then a local legend. Research not only included books and old newspaper articles, but gathering oral history from people like 105-year-old Bernice Martin, who said that MLK attended her church in Simsbury, The First Congregational Church; and had been recruited to sing in the choir.

The students put their findings in a video, Summers of Freedom, which was covered by the CBS Evening News and other major outlets; and residents then followed with a grassroots citizen petition process and special town meeting that put the question of the Meadowood purchase on a referendum in May 2021.

Residents authorized $2.5 million for the purchase and preservation of the 288-acre Meadowood property by a resounding 87 percent. The property has since been nominated for historic designation.

The stage had already been set for that referendum on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in January, with the unveiling of a permanent MLK memorial. The memorial was made up of five glass panels representing the different stages of MLK Jr.’s life. It was made possible by groups of Simsbury High School students, who raised $150,000. It will now be listed as a destination on Connecticut’s Freedom Trail.

If you have read any of my past columns, you know that I enjoy reading history; and especially enjoy ferreting out instances of the unique. I anticipate expanding on the folklore that surrounds the life of General Israel Putnam, cited above as an “influencer,” who played a significant role in increasing the popularity of cigars.

A prominent member of the expat community and chronicler of the local zeitgeist lamented, after publishing the first essay in this series, “The British role in the whole [tobacco] business is not a glorious one”!

All that said, I have never used any tobacco product.

Sources:

- Connecticut Valley Tobacco Historical Society

- Connecticut Valley Agricultural Museum

- Preservation Connecticut

- Simsbury and Windsor Historical Societies

- The Connecticut Agriculture Experiment Station

- Holt’s Cigar Company

- Cigar Aficionado

- New York Times, Nov. 12, 2021; article by Corey Kilgannon

Editor’s Note: This is the opinion of Thomas D. Gotowka.

About the author: Tom Gotowka’s entire adult career has been in healthcare. He will sit on the Navy side at the Army/Navy football game. He always sit on the crimson side at any Harvard/Yale contest. He enjoys reading historic speeches and considers himself a scholar of the period from FDR through JFK. A child of AM Radio, he probably knows the lyrics of every rock and roll or folk song published since 1960. He hopes these experiences give readers a sense of what he believes “qualify” him to write this column.